As Greek fatigue threatens to overcome us all, it may be useful to draw comparisons between Ireland and a country other than Greece. There have many occasions when comparisons have been made between the differing approaches of Ireland and Iceland to their respective banking crises. One indicator that is frequently used to aid the comparison is the unemployment rate in both countries.

The IMF put unemployment in Iceland at 7.5% in contrast to 14.5% in Ireland – a rate that is almost twice as large. This formed part of a recent presentation from Paul Krugman. You can watch a 15-minute video of Krugman deliver the presentation here (go to 52:00 of the Session II: Road to Recovery video).

However, this unemployment snapshot only paints a partial picture.

Icelandic unemployment is significantly lower, but it also started from a much lower level. The unemployment rate in Iceland was 7.5 times larger in 2010 than it was in 2007 (1.0% to 7.5%). In Ireland the increase was 3.1 times (4.6% to 14.5%). In Iceland, the unemployment rate increased by 6.5 percentage points, here it rose by 9.9 percentage points. There is no doubt that unemployment in Ireland is higher and has risen by more than unemployment in Iceland.

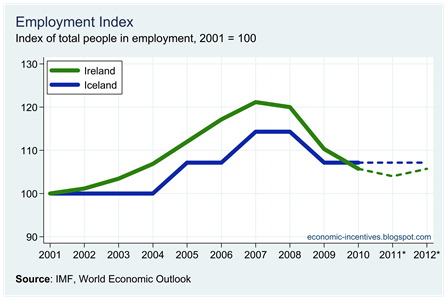

As Krugman does, we can account for migration by looking at changes in employment. Since 2007, the number of people employed in Ireland has fallen further, but the Icelandic figures is somewhat invariant because of the units used by the IMF (tens of thousands with Icelandic employment forecast to be completely unchanged at 150,000 over the four years from 2009 to 2010).

Since 2007, employment in Iceland has fallen 6% while in Ireland the fall has been over 14%. However, it is hard to argue that this is as a result of the response to the crisis given the huge collapse that has occurred in construction employment in Ireland. Since 2007, there have been more job losses in the construction sector in Ireland than there are people working in Iceland.

What happens if we move on from unemployment and employment and look at other macroeconomic indicators. Krugman doesn’t seem to be a fan of using GDP for small open economies but it seems a reasonable place to start.

Judging by the IMF forecasts the “roads to recovery” of Ireland and Iceland are almost side-by-side. There are also graphs of an index of real GDP per capita and GDP per capita at PPP by clicking the links.

An interesting picture begins to emerge if we look at the relative performances of nominal GDP.

There is a huge break from the onset of the crises in both countries in 2007/08. Clearly, with the real GDP indices of both countries tracking each other over the same period there must be some significant price effects. This can be seen if we look at an index of consumer prices.

Annual inflation in Iceland has been higher than in Ireland since 2004 but this gap ballooned in 2008 when Icelandic inflation was 18% compared to just over 1% in Ireland. The annual inflation rates can be seen here.

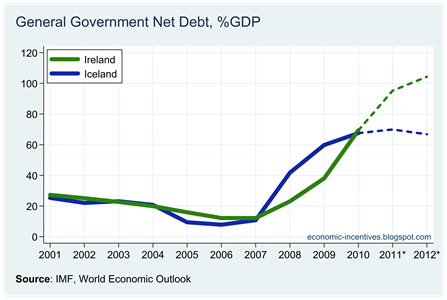

Next is the gross government debt to GDP ratios for both countries.

Spot the difference! In 2007, both countries had a gross debt to GDP ratio of just under 30%. By 2010 both had ballooned to around 95%. And note that the Ireland ratio was pulled up with the price deflation in the denominator, while Iceland was experiencing inflation of almost 20% in its denominator. The Icelandic debt level rose faster and is forecast to moderate at a lower level. The same can be seen for government net debt.

Iceland does better when the comparison is based on unemployment. The comparison is not so positive if GDP, inflation and government debt are included. The same is true if we look at the current account of the Balance of Payments.

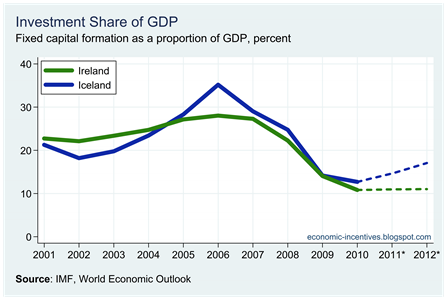

The Icelandic current account has been improving but this is more to do with a collapse in imports rather than a rise in exports. Finally here is the investment share of GDP in both countries.

All in all, there does not seem to be a lot to separate the two countries. Both have had banking collapses. Both have struggled to deal with them. Iceland is perceived as being in a better position but that is not really borne out in the IMF data.

Tweet

No comments:

Post a Comment