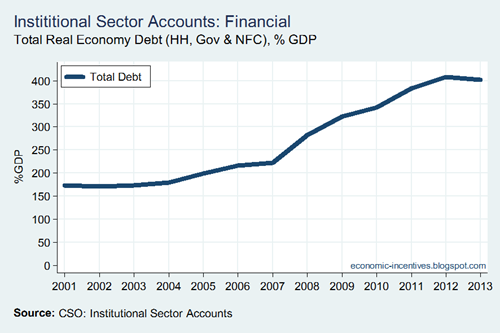

A recent report on debt and deleveraging from McKinsey attracted some attention, due in part to the location of Ireland in a few of the key charts. Ireland is shown to have had the largest increase in debt as a proportion of GDP since 2007 with the overall level of debt in the economy put at 390 per cent of GDP.

We have looked at the relevance of such statistics many times before – such as here, here and here. We will do the same here but using data from the Institutional Sector Accounts and revised Balance of Payments statistics being produced by the CSO under BPM6.

The measured level of debt in Ireland rose steadily from 2003 to 2007 during the credit bubble but then somewhat counter-intuitively accelerated rapidly when the crash hit in 2008.

Obviously, government borrowing accounts for some of this but the scale of the increase is significantly greater than can be explained by the fiscal deficits. As can be seen in the chart below the debts of non-financial firms also accelerated in 2008 which runs counter to the narrative of the busting of the credit bubble.

The 2013 figures in the above charts are:

- Household Debt: 96% of GDP, €168 billion

- Non-Financial Corporate Debt: 174% of GDP, €303 billion

- Government Debt: 132% of GDP, €232 billion

- Total Debt: 402% of GDP, €703 billion

The measure of government debt includes the debts of the IBRC which was initially left in the financial sector when it was established but has since been re-categorised as part of the government sector. This was a significant factor in 2011 and 2012 but the liquidation of the IBRC that began in February 2013 has reduced its impact on the government’s balance sheet.

Two key issues need to be addressed:

- Is the hole really €700 billion? If it is we’re goosed.

- What explains the rise of the red line (NFC debt) in the above chart?

We answered these questions before but here we will look at them using revised balance of payments and international investment data from the CSO.

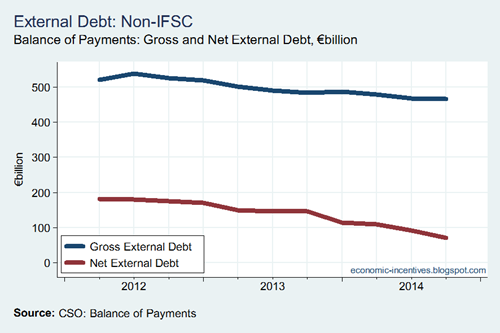

An important measure for any economy is gross external debt: the amount borrowed from foreigners. For Ireland there is the complication of the IFSC (which has external liabilities – and assets! – of several trillion). However, the CSO also provide this data excluding the impact of the IFSC.

The updated data series is not lengthy but we can see what has been happening recently. Ireland’s gross external debt is falling, albeit slowly, but is still around €465 billion. That is a big hole.

The measure of net external debt accounts for the foreign assets in debt instruments held by residents. That has fallen below €100 billion. However, we cannot say that those who who have the foreign debt liabilities also hold the foreign debt assets.

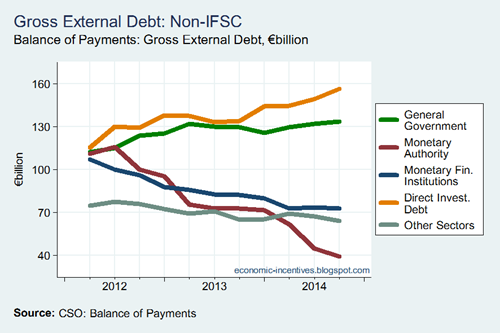

We can examine this by looking at the sectoral breakdown of the gross external debt.

This is an instructive breakdown. The continued increase in the external borrowings of the government sector well understood. It can be seen that the external liabilities of the monetary authority (Central Bank of Ireland) and monetary financial institutions (the banks) have been declining rapidly as the banks deleverage and repair their balance sheets.

What is most notable is the increase in external debt associated with direct investment which has risen to €160 billion (almost 100 per cent of GDP). This is the external debt of MNCs in Ireland. This is the sector that has shown the greatest increase over the past few years and is what accounts for the increase in the red line in the second chart from the top.

So that answers one question. NFC debt is increasing because of the activities within the MNC sector – mainly intra-group treasury operations.

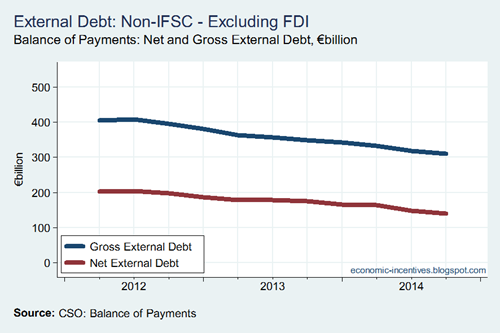

Using these we can reconsider the gross and net external debt figures but excluding the impact of FDI. Doing so gives the following result.

Excluding the external liabilities of MNCs reduces Ireland’s gross external debt to around €300 billion (while excluding the external debt assets of the MNCs actually increases Ireland’s net external debt to €140 billion). The downward slope of the blue here contrasts with the upward slope of the blue line in the first graph. What we see here is a better indicator of where we are and where we’re going.

A gross external debt of €300 billion is around 175 per cent of GDP. This is a significant external debt burden but is a long way from 400 per cent of GDP. There has also been a rapid fall in this measure of external debt which has been reduced by around €100 billion in early 2012 when it was just over €400 billion.

Obviously the overall amount of debt in the economy is greater than €300 billion but the money owed to non-residents is a key indicator. The banking sector in Ireland moved to a net international investment position of near balance after the collapse(though was largely replaced by an external debt by the Central Bank which has since reduced). While we have unresolved domestic issues with household debt through mortgages and debts in the SME sector our external debt position has improved markedly (and probably wasn’t as bad as some headline figures may have suggested).

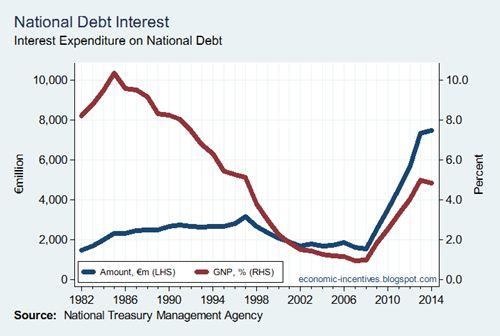

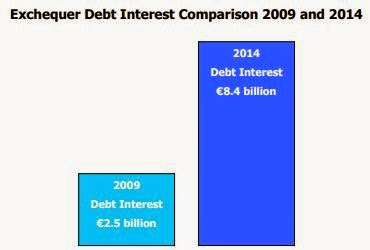

A major determinant of any default event is external debt and outward interest flows. The reduction in external debt and the extremely low interest rates mean that this outflow is declining.

How do we make it fall further? There are four steps that can be taken.

- Stop borrowing more from abroad. The government sector is the only domestic sector that continues to borrow more from abroad. This may be drawing to a close.

- Repay debt from income. Ireland is running a current account surplus which can provide the resources to repay debt.

- Repay debt by selling assets. Asset sales to non-residents are likely a significant factor in the recent in the external debt fall.

- Default.

Even if the rate of reduction moderates somewhat using steps 1, 2 and 3 our gross external debt should be down to 100 per cent of GDP by the end of the decade and may be even lower. Yes, we’re in a hole (one that is around 175 per cent of GDP) but we’re climbing out of it.

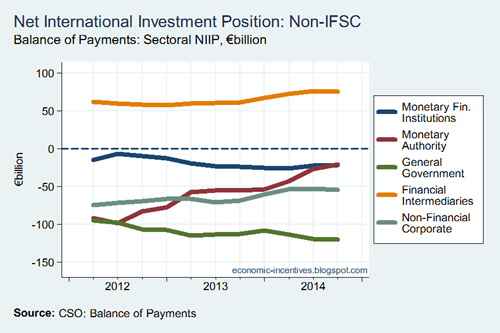

This improvement in our external position is also evident if we look at the net international investment position which accounts for all external assets and liabilities and not only those in debt instruments. First, here’s the NIIP by sector (excluding the IFSC of course).

The continued deterioration in the position of the government sector is evident as is the improvement in the external position of the Central Bank. Financial intermediaries is likely dominated by the pension savings of Irish residents which are invested abroad.

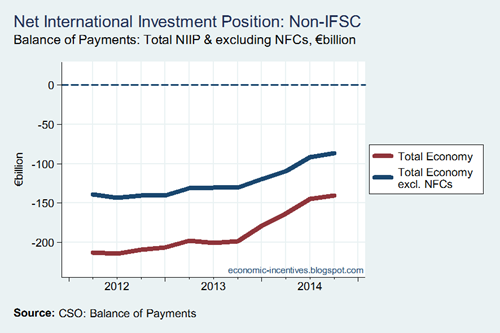

And finally here’s the overall NIIP for the Irish economy with the NIIP shown excluding NFCs also shown (as it is the MNCs that dominate the external position of the NFC sector).

It can be seen that the NIIP excluding NFCs has improved by about €50 billion over the past 2.5 years. This is less than the €100 billion reduction in our gross external debt. This can arise if foreign assets are sold to repay foreign debt (meaning the NIIP is unchanged). Foreign assets by sector (bar NFCs) are shown in the chart here – yes, the banks have reduced (sold?) some foreign assets.

Still a bit to go until we get to zero but we’re getting there. I’d also guess the CSO still have a bit of work to go in moving to ESA2010 and BPM6 but they’re getting there too.