The

announcement by Facebook that it was “moving to a local selling model” has been met with some breathless reaction with some thinking it will lead to

sleepless nights. There are a couple of reasons why such a reaction to this announcement may be excessive or why having sales recorded in the location of the customer isn’t the tax-changing panacea that some have made it out to be. Anyway, here’s the key part of the Facebook announcement:

Today we are announcing that Facebook has decided to move to a local selling structure in countries where we have an office to support sales to local advertisers. In simple terms, this means that advertising revenue supported by our local teams will no longer be recorded by our international headquarters in Dublin, but will instead be recorded by our local company in that country.

There are a couple of reasons for a more reflective reaction. First, Google announced that it was moving to such a model back in January 2016 while Facebook itself has been booking UK sales with its UK subsidiary since April 2016. Neither have caused the sky to fall in.

When HMRC concluded its six-year audit of Google in the UK in January 2016 Matt Brittin, Head of Google in Europe, gave an interview to the BBC:

“Today we announced that we are going to be paying more tax in the UK.”

"The rules are changing internationally and the UK government is taking the lead in applying those rules so we'll be changing what we are doing here. We want to ensure that we pay the right amount of tax."

The firm has now agreed to change its accounting system so that a higher proportion of sales activity is registered in Britain rather than Ireland.

"We are paying £130m in respect of previous years when the rules were to pay in respect of profits you make in a country and then going forward we will also be paying in respect of sales to UK customers," Mr Brittin said.

Asked whether the back-payments showed Google's critics were right that the company had avoiding paying tax in the past, Mr Brittin replied: "No."

He continued: "We were applying the rules as they were and that was then and now we are going to be applying the new rules, which means we will be paying more tax.

"I think there was concern that international companies were paying only in respect of profits that they make and those were the rules and the pressure was to see us pay in respect of the sales we make to UK customers - and the same for other companies.

"So, we are making a change because we want to continue to comply with the rules and the rules are changing."

I think the last word of the second last paragraph should be “countries” or be extended to “Google companies in other countries”. So there is no precedent with the Facebook announcement. Google got there two years before them.

And Facebook have been booking sales in the UK for over a year now as it states in

the recently-filed 2016 accounts for Facebook UK Ltd. In those accounts we are told:

The principal activity of the company in the year under review was that of providing sales support, marketing services and engineering support to the Facebook group and to act as a reseller of advertising services to larger UK customers. The company’s function expanded to include the advertising reseller business in respect of large UK customers on 1 April 2016.

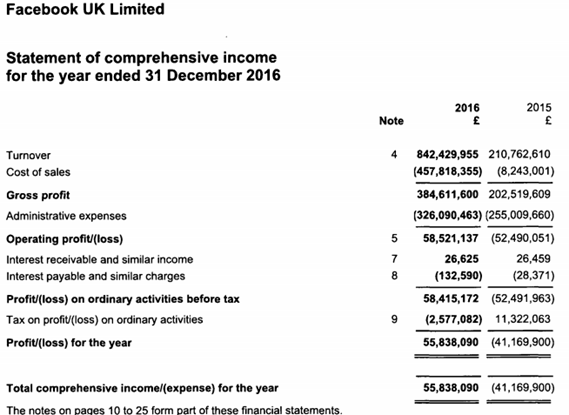

Revenue for the year amounted to £842,429,955 (2015: £210,762,610), which is an increase of £631,667,345 on the value of services provided in 2015. This increase was attributed to the commencement of advertising reseller services from 1 April 2016.

The impact of this can be seen in the income statement for Facebook UK Ltd.

The first line shows the £632 million increase in turnover but this is immediately followed by a £450 million increase in the cost of sales. After a £75 million increase in administrative expenses (mainly staff costs), all told, in 2016 Facebook UK Ltd. ended up with a profit of £58.4 million and a resultant tax bill of £2.6 million. [Insert meaningless calculations of tax as a proportion of revenue around here.]*

The jump in the cost of sales figure is linked to the company becoming a reseller in April 2016. In 2015, the company didn’t have any third-party sales. All of its revenue was derived from providing marketing and support services to Facebook Ireland Ltd. In 2016, it recorded the revenues from sales to the UK customers it dealt with directly but like with any company that doesn’t make the produce or service it sells it had to buy them from a supplier.

There have been plenty of calls that revenues should be recorded where the customer is located. And it could be that Facebook is reacting to the possibility that the implementation and/or interpretation of the BEPS proposals could mean that Facebook Ireland Ltd would be deemed to have a “permanent establishment” through the local company and that any sales done through that PE would be recorded in that country anyway. By acting now to record the sales in the local companies Facebook is controlling the changes – albeit incurring significant cost to do so.

The recording of sales in the local companies is fine but it must be remembered that the corporate income tax is paid on profit not revenue. Revenue only translates into profit to the extent that a company has risks, functions or assets that add value. And if a company doesn’t even make the product it sells it must buy it. In fact, because of this it may be that the aggregate revenue-profit-tax outcome that arises through all these local companies will not be significantly different than what is achieved through the central company in Ireland now. There may be differences in where tax is paid but it will be interesting to see if it results in more tax being paid overall.

Anyway, back to the need for companies who don’t make what they sell to buy it. This can be from a related or third-party supplier but regardless of the relationship between them the price should be the same, i.e. as based on the arm’s length principle. So if Facebook UK is selling advertising on a platform that is owned by someone else it must pay the owner of the platform (or its licensee) for the right to sell that advertising or buy the advertising space before selling it on. The latter appears to be what Facebook is doing in the UK and this is the cost of sales figure that offsets most of the revenue increase that resulted from recording the sales locally in the first place.

Who is Facebook UK buying the advertising space off? We don’t know who this is but a good guess is probably the company that sold the advertising space to these customers the previous year. And we all should know who that was. So while the third-party sales may be recorded with the local company there will still be intra-company sales recorded in Ireland. The final paragraph of the Facebook statement is not without its significance:

Our headquarters in Menlo Park, California, will continue to be our US headquarters and our offices in Dublin will continue to be the site of our international headquarters.

The revenues will still end up in Dublin it’s just that some third-party sales will be initially recorded with local companies. Third-party sales to customers that do not have a local company as well as sales in those countries that do from customers who do not interact with the local companies will continue to be recorded in Ireland.

As the only customers in question are those who interacted with their local company rather than Dublin anyway there is unlikely to significant change to the activities carried out by the staff in Dublin. It is not as if there are staff in Dublin who will lose key customers or accounts because of this change. They were been serviced by the local companies as it stands. One of the important, and valid, criticisms of the old structure was that close on the only thing that happened in Dublin relating to these customers was the conclusion of the sale – the virtual signing of the contract. The new structure better reflects Facebook’s selling activities.

It is also not clear how this change the amount of Corporation Tax that Facebook will pay in Ireland. It is likely that Facebook Ireland Ltd is currently remunerated on some form of “cost-plus” basis with the main cost included in the calculation being the staff costs. If there is no significant change in the activities of Facebook in Ireland, its cost here could remain similar and so too could its Corporation Tax liability here.

There may, however, be changes to the risks, functions and assets that Facebook has in Dublin but they are not detailed in the short statement issued by the company. It could be that headlines like “Facebook will stop using Ireland as a global hub for tax and revenue” are wide of the mark.

As we have seen this is because it is likely that the advertising services sold in the local markets will still originate with the Irish company and, crucially, we don’t know what Facebook is going to do with its licenses and intellectual property.

As we looked at before (here and here) the transfer of these licenses out of the US is subject to an investigation by the IRS. At issue there is the price paid for those licenses but the existence of them to grant the rights to sell advertising on the Facebook platform outside the US is likely to continue. We don’t know where those licenses are currently held but some indications point to the Cayman Islands.

Unless Facebook are going to move significant DEMPE functions (developing, enhancing, maintaining, protecting or exploiting intangible assets) then payment to a cash-box in the Caymans may not be allowed as a deduction for tax purposes when the full implementation of the transfer pricing changes in the BEPS proposals comes into effect.

Facebook will likely seek to move its IP to a location where these DEMPE functions are located. An obvious choice would be the US where the main innovation and R&D of the company takes place. But even the proposed changes currently hurtling through Congress are unlikely to make that sufficiently attractive for companies who have managed to get part of their IP outside of the US.

Another alternative is Ireland. We have already seen significant onshoring of IP and it is possible we will see more. It would seem natural to co-locate the license to your international sales with your international headquarters. Hence, the possible significance of that final paragraph in the company’s statement.

The thing is we just don’t know. Maybe the advertising sold by the local companies won’t originate in Ireland. Maybe the IP won’t be onshored here. But until we know that let’s keep a lid on the breathless reactions.

There are risks to Ireland’s FDI model but I’m not sure ICT companies moving to a local selling model for some customers is one to knock us over. There are tens of billions worth of goods and services sold from Ireland and most is via intra-company sales rather than sales to third-party customers. We had €14.7 billion of exports to Belgium last year of which €13.5 billion were pharmaceuticals. I don’t think they were all taken by Belgians.

There could be benefits for Ireland. As the sales are being recorded in these countries they will get first dibs at taxing the resulting profits. If they think they’re not collecting the “right” tax from these sales (whatever that may be) the first bout of finger-pointing should be domestic.

Of course, if the products or services originate in Ireland and/or the companies have their IP in Ireland then we will be next in line. And maybe like India is attempting with Google countries may try to describe the payments to Ireland as royalties rather than sales revenues possibly bringing withholding taxes into play (for some non-EU countries at least). Those sleepless nights may arrive yet.

* It’s 0.3% by the way.