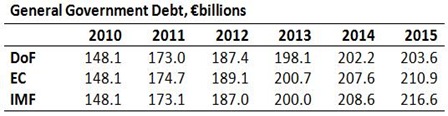

There has been a huge amount of comment on debts, liabilities and losses in the Irish economy. The most high profile of the recent estimates has been that the public debt will be “closer to €250 billion” by 2014. In my view this is an over-estimation and the 2014 public debt is likely to be around €200 billion. This is not a difference that is “immaterial”.

A story based on the premise that our debt is unsustainable needs a debt figure of €250 billion to remove all doubt that the debt is sustainable. With a debt of €200 billion the picture is not so clear cut. €200 billion is still a huge burden and is a monumental amount of debt. The problem for the doomsayers is that it is a debt that the Irish economy may be able to carry.

There is no certainty either way but with a projected debt level of €200 billion you need to weigh the costs and benefits of a drastic course of action, be that a sovereign default, an immediate budget balance, exit from the EU/IMF package or maybe even all three at once! A debt of €250 billion would make such cost-benefit analysis largely obsolete because a debt of €250 billion is unsustainable and drastic action would be required.

If the debt is going to be €200 billion then a more considered approach must be taken because the certainty of insolvency is removed. Thus the difference between a debt of €200 billion and a debt of €250 billion is very much “material”. Could the debt in 2014 be €250 billion?

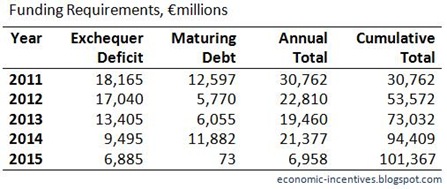

At the end of 2011, the internationally recognised measure of public indebtedness, the General Government Debt (GGD) will stand at €159 billion. After years of fantasy projections that were wide of the mark, it now seems that the Department of Finance has got a handle on estimating the country’s medium-term deficits. The projections are that for the period 2012 to 2014, the deficits will add about €34 billion to the General Government Debt. Given the horrendous state of the public finances it is hard to envisage a further deterioration that would see a significant increase in the amount of borrowing required to run our public services, but some slippage is possible.

This will bring the debt to around €195 billion, still €55 billion short of the total required for Armageddon. As it stands we are told the covered banks will need another €24 billion of capital. About €20 billion of this will come from the State. Of this, €10 billion will come from the further decimation of the savings built up in NPRF. This will not add to our borrowings. The other €10 billion will come from some of our existing cash balances which again will not increase our borrowings. It is likely that the amount borrowed for this recapitalisation will bring the 2014 debt to around €200 billion, give or take.

Is there another €50 billion of debt out there to bring about the Day of Judgement? This debt can only come from losses in the banking sector which has now been umbilically linked to the State. However, rather than looking for another €50 billion of debt to be created by the banking collapse I think it is worthwhile to look back and see what levels of losses have already been accounted for, and whether it is likely that these are an underestimate of the final loss outcome.

To this end we will just consider two sources of losses. A more forensic analysis would probably reveal more losses that have been accounted for but we can start with these two processes.

- Losses generated by the transfer of developer loans to NAMA and

- Losses covered by the most recent set of stress tests on the four “viable” covered banks.

The losses crystallised by the NAMA process are very easy to work out. By the end of March this year, NAMA had acquired €72.3 billion of loans from the five participating banks (PTSB does not have a developer loan book) and had paid €30.5 billion for them. Thus, the banks were forced to apply €41.8 billion of losses to their balance sheets. These losses were covered by the earlier recapitalisations that saw €46 billion committed to the banks. The borrowing that this required is all included in the €200 billion debt estimate.

So what level of losses was covered by the recent stress tests? The stress tests looked at the entire loan books of the four banks examined and provided loan loss provisions. Here are the adverse scenario lifetime loan losses estimated by BlackRock Consultants. The number in brackets is the percent of the loan book at the end of 2010 that these losses comprise.

- Residential Mortgages: €16.9 billion (12.0%)

- Corporate Lending: €2.5 billion (5.8%)

- Small and Medium Enterprise Lending: €7.0 billion (19.0%)

- Commercial Real Estate Lending: €10.3 billion (25.5%)

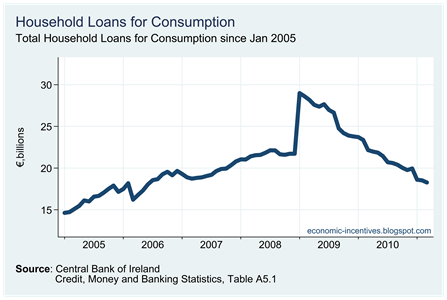

- Consumer Lending: €3.5 billion (27.1%)

- TOTAL: €40.1 billion (14.6%)

These are not the only losses covered by the stress tests. The banks are also being forced to deleverage by selling non-core assets. This will require the sale of €72.6 billion of at an estimated loss of €13.2 billion. BlackRock estimate that this loan book would have lifetime losses of €3 billion. All of these losses are covered by the €24 billion recapitalisation. Again, the borrowing this €24 billion requires is included in the €200 billion debt estimate.

The reason the required capital is lower than the projected losses is because 1) the banks already have an existing capital stock, 2) the banks had already incorporated some loss provision on their balance sheets and 3) these are lifetime losses some of which can be met by the future operating profits of the banks so the current capital injection covers losses expected to crystallise over the next three years (€27.7 billion).

So from these two sources we have €41.8 billion of loan losses on the transfer by five banks of their developer loans to NAMA, and €43.1 billion of loans losses included in the stress tests of the four viable banks. This means that nearly €85 billion of loan losses (and €95 billion of losses in total) have been accounted for in the covered institutions.

There will also be losses in the banks not covered by the guarantee that have been lending into the Irish economy: Ulster Bank, ACC, Rabodirect, Bank of Scotland, etc. These losses are of little concern to us, but they do increase the amount of losses already accounted for as this huge banking collapse unwinds. There will also have been other losses in the covered banks that will have been worked through outside of the NAMA and stress test processes.

This means that the total amount of loan losses already accounted in the system is somewhere in the region of €100 billion. Is there anyone who has suggested that Irish banking losses will be €150 billion? Anyone? These are the level of losses that are needed if Ireland’s public debt is to reach €250 billion by 2014.

This time last year Prof. Morgan Kelly forecast that “between developers, businesses, and personal loans, Irish banks are on track to lose nearly €50 billion if we are optimistic (and more likely closer to €70 billion)”. Prof. Kelly deserves huge credit for his foresight about these losses in the banks. He would be right about the public debt if he had taken his original figure and pushed it up to €100 billion.

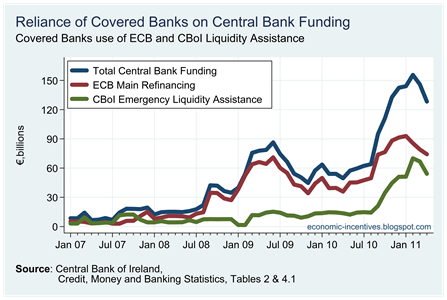

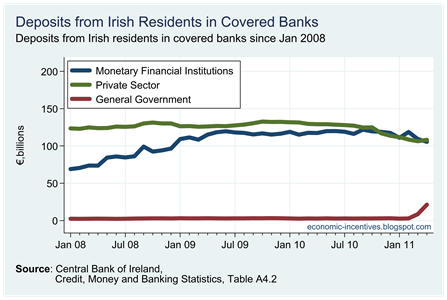

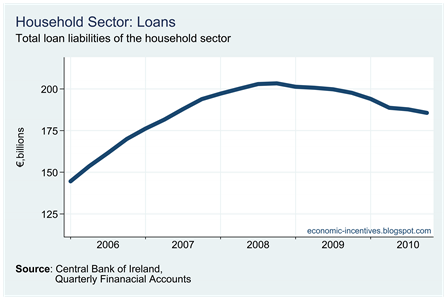

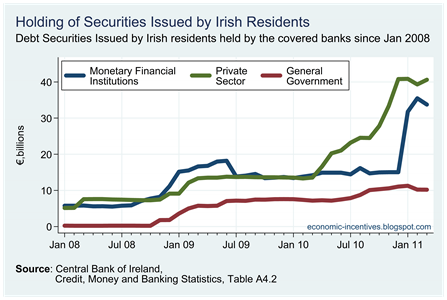

Some estimates of public debt add in some selected liabilities of the banks. Banks have huge liabilities: depositors, bondholders and central banks. But the banks also have huge assets: primarily loans. Data from the Central Bank show that the covered banks had total liabilities of about €430 billion at the end of December 2010. These liabilities will only become a problem for the State if the €430 billion of assets the banks also have on their balance sheets generate losses that mean the liabilities cannot be met. These losses are most like to occur in €294 billion of loans to customers that the banks have. Account has already been made for €85 billion of such losses.

The liabilities sometimes also include the €30 billion used to set up NAMA. Again there is an asset to offset this liability. What matters for the debt is whether NAMA makes a loss. NAMA itself forecasts a profit of nearly €1 billion. This is probably a little optimistic but given current property prices it is likely that NAMA would make a loss of around €3 billion. The future direction of property prices will dictate the final outcome but it impossible for it to be anything approaching the current liabilities of NAMA.

If Ireland’s public debt is to be €250 billion as forecast by Prof. Kelly, another €50 billion of banking losses have to materialise in the six covered banks. If Ireland’s public debt is to be €250 billion by 2014 we are bust.

If these €50 billion of banking losses cannot be found, and Ireland’s public debt in 2014 is going to be closer to €200 billion, then we need a reasoned debate on how to address this huge problem that we face. I’d like to think that Prof. Kelly is somewhere enjoying the hysterical reaction that his “back of a fag box” analysis has generated. I’d like to think that the rest of us can realise that it is wrong.

If someone thinks Ireland’s public debt is going to be €250 billion in 2014 they should tell us how they think this will happen. The General Government Debt is going to be around €200 billion in 2014. Of this, we will have brought about quarter of it with us into this crisis, a half will be due to funding the deficits from 2008 to 2014 with only the remaining quarter due to the banking disaster. Cutting loose the banks could not possibly lead to a situation where “at a stroke, the Irish Government can halve its debt to a survivable €110 billion”. The banks are not the biggest source of our debt.

We need to move on to that reasoned debate and determine the best course to take in getting out of this huge problem. This will mean some of the drastic measures listed above should be considered but we are still short of the stage where these are a necessity. It is still likely that we can survive this crisis.