The most significant announcement on Corporation Tax in the recent budget was the planned introduction of a ‘knowledge development box’. The changes to the residency rules under the heading of the “double-irish” will be ineffective in changing tax outcomes and the profits, as well as the low-tax outcomes, will remain offshore. A blind-eye could not be turned if similar low-tax outcomes were achieved using an onshore ‘knowledge development box’.

In the Financial Statement the Minister for Finance said “I plan to legislate for it in next year’s Finance Bill or as soon as EU and OECD discussions conclude.” A significant element of these discussion is this joint Germany-UK statement on patent boxes.

It is not clear what impact this will have on Ireland. The Minister for Finance’s intention that “the Knowledge Development Box will be best in class and at a low competitive and sustainable tax rate” is a relative concept. When trying to examine this it worthwhile to look at the level of R&D expenditure in Ireland.

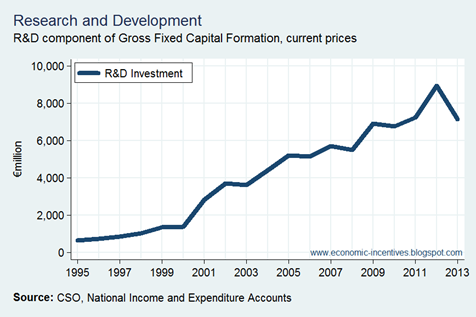

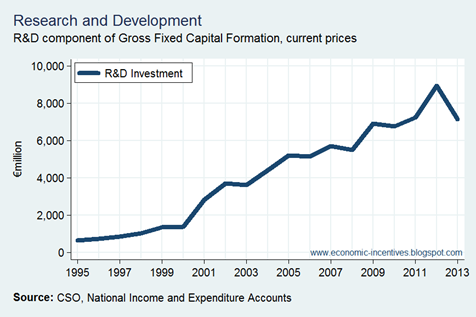

The most significant change in ESA2010 is the reclassification of R&D expenditure. In essence it has been moved from intermediate consumption to capital investment. The revised NIE accounts provide figures on GFCF (Gross Fixed Capital Formation) in R&D back to 1995.

The six per cent rise in the level nominal GDP arising from the introduction of ESA2010 is almost entirely due the capitalisation of R&D expenditure as the CSO explain here. The estimate of 2013 nominal GDP was revised from €164 billion under ESA95 to €175 billion when ESA2010 was applied.

While there is a huge amount of R&D expenditure in Ireland (€7 billion in 2013) but there is little evidence of activity resulting from it. The reason for this is that most R&D in Ireland is imported. The expenditure comes from Ireland but the activity takes place somewhere else.

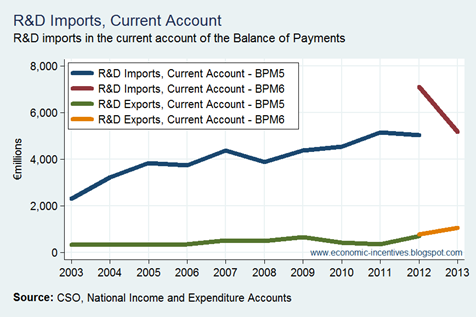

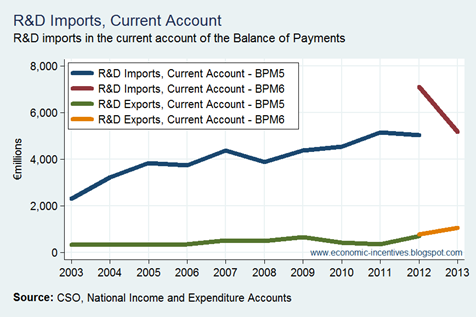

We can see this in the Balance of Payments where R&D imports are recorded (payments made from Ireland to pay for R&D activity elsewhere). International standards for the collection of Balance of Payments data have also being revised and the CSO have moved from applying BPM5 (Balance of Payments Manual) to BPM6. For that reason we get two measures in the following chart as the CSO have not published revised historical data using BPM6.

The main difference for R&D in BPM6 is that outright purchases of patents are now included in the current account whereas under BPM5 such transactions were in the capital account. The €2 billion difference between the BPM5 and BPM6 R&D imports figures for 2012 is due to a large acquisition of a patent by an Irish-resident company.

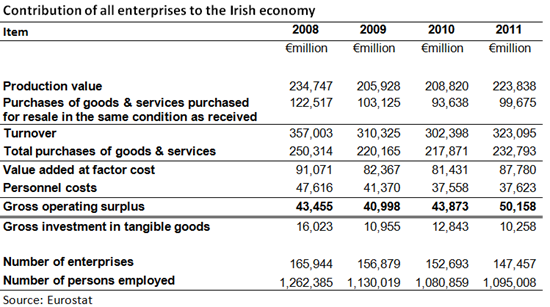

There is also a small amount of R&D exports from Ireland and this series seems relatively unaffected by the change from BPM5 to BPM6. It is the net amount between exports (R&D assets going out) and imports (R&D assets coming in) that contributes to gross fixed capital formation (GFCF). The following table gives a breakdown of the R&D component of GFCF shown in the first chart for the past four years (all figures in €millions).

Net capital transfers are the irregular outright purchase and sale of patents and other IP. Net service imports mainly reflects MNCs paying for R&D with funds from their Irish branch/subsidiary. This allows the Irish MNC to contribute to the cost of the R&D and also to use the resulting patent or IP. This can be achieved through things like cost-sharing agreements. Here is a short description:

An agreement between two parties to share the cost of developing an intangible asset, such as computer code, production methods, or patents. Such an arrangement is used to reduce or avoid taxes on the transfer of assets. For example, if a parent company wanted a foreign subsidiary to use one of its patents, tax authorities might consider the transfer a taxable transaction. By establishing a cost sharing agreement, the parent company and the subsidiary share in the cost of developing the patent, so that both are entitled to use it, and it is not transferred from one to the other.

The final sub-part of the above table labelled “in-house R&D” refers to R&D activities in the private sector that take place domestically (i.e. within Ireland) and also in the public sector such as in health and education.

The table clearly shows that the most significant contributor to R&D in Ireland is R&D imported by the MNCs. It is important to note that this only has a once-off level effect on GDP. Up to this year these R&D imports where included in the national accounts (subtracting from GDP). It is only with the introduction of ESA2010 that these R&D imports are counted as part of gross fixed capital formation (adding to GDP). From now on the net or growth effect will be zero as the positive investment effect will be offset by the negative import effect. It will affect the composition of GDP though.

How do these R&D expenditures relate to the Germany-UK statement on preferential IP regimes? Here is a key extract (emphasis added):

The OECD Forum on Harmful Tax Practices (FHTP) has led work in relation to BEPS Action 5, Countering Harmful Tax Practices More Effectively, Taking into Account Transparency and Substance. Work within the FHTP has led to the development of proposals for new rules, known as the Modified Nexus approach, based on the location of the R&D expenditure incurred in developing the patent or product. This approach seeks to ensure that preferential regimes for intellectual property require substantial economic activities to be undertaken in the jurisdiction in which a preferential regime exists, by requiring tax benefits to be connected directly to R&D expenditures.

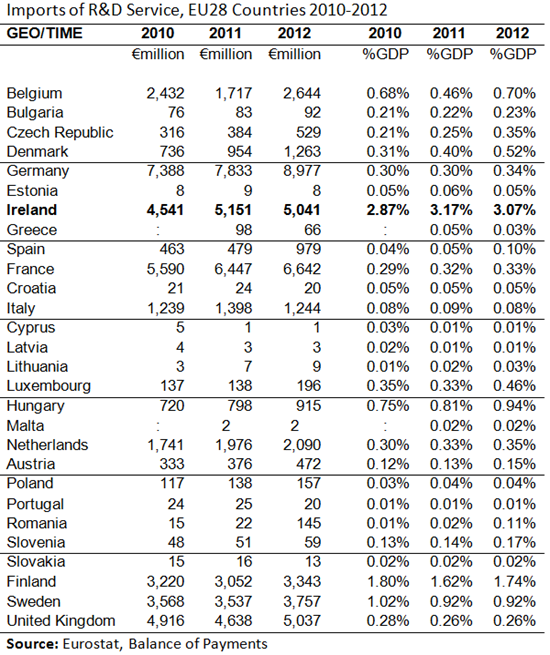

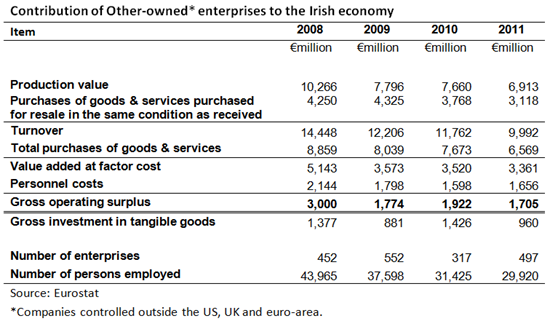

One source of R&D expenditure is domestic or “in-house” R&D activity. Unfortunately, national accounts data using ESA2010 for all EU countries are not available from Eurostat. From the CSO we know that such “in-house” R&D expenditure is relatively small in Ireland.

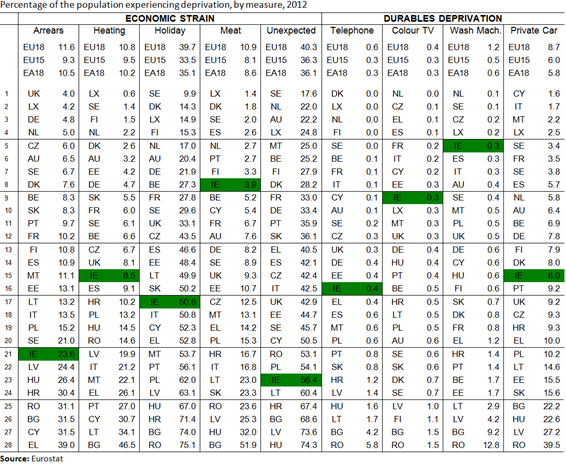

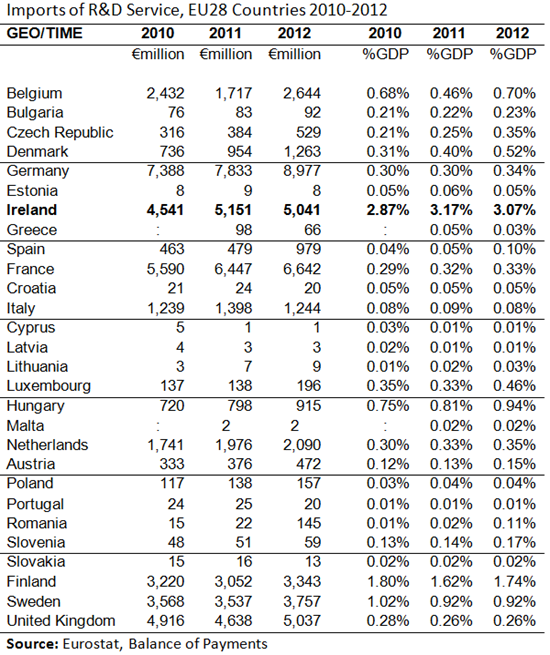

The other source is net R&D imports. This is the main contributor to R&D GFCF in Ireland. We can use Eurostat Balance of Payments data to see how much of an outlier Ireland is. In 2012, in nominal terms, Ireland had the third highest level of R&D imports, behind only Germany and France with the UK on practically the same amount.

It is when you look at the figures as a proportion of GDP (albeit using the ESA95 figures which Eurostat provides) that we can see just how much of an outlier Ireland is. These expenditures are equivalent to around 3 per cent of Irish GDP. Finland is the only other country with a level above 1 per cent of GDP.

If the R&D expenditure from Ireland is counted as “qualifying expenditure” for these patent boxes then the ‘knowledge development box’ announced in the budget has the potential to be a significant component of Ireland’s Corporation Tax regime – whether this is positive or negative depends on one’s position of the issue.

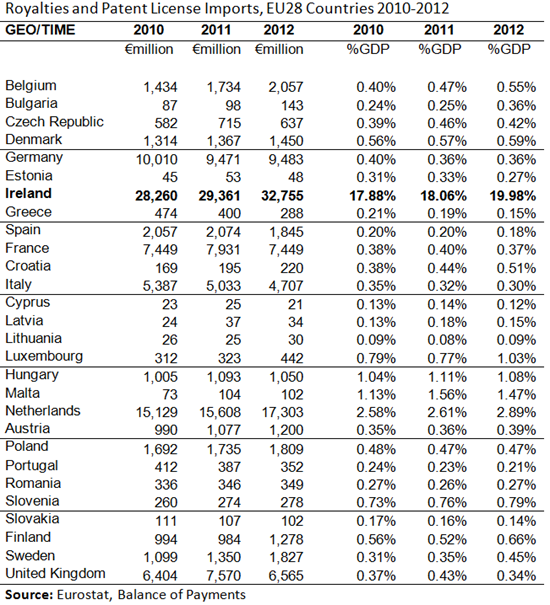

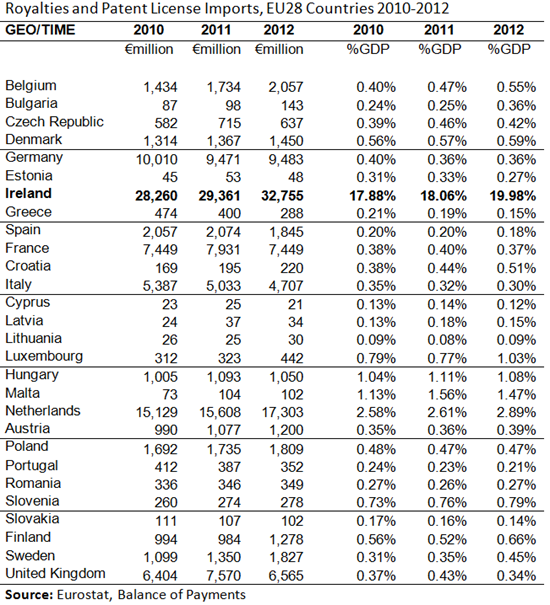

However, this is only one part of the potential of this scheme. Thus far we have looked at the R&D expenditure that currently takes place here. There is also the R&D expenditure that might take place here. We know MNCs do not generate their IP here but they do exploit it here. The largest payments from Ireland for IP are not R&D cost-sharing expenditures but patent royalties. When it comes to these in a European context Ireland is off the chart.

In Ireland these outbound payments are the equivalent of almost 20 per cent of GDP. The next highest is the Netherlands but the figure is less than 3 per cent of GDP.

Why are these significant in terms of a ‘knowledge development box’ when these are payments for the use of IP not its development? These payments are made to companies which own the intellectual property. In many cases these will be Irish-registered companies (though heretofore non-resident for tax purposes). This is the two Irish company structure in the “double-irish”.

The big change for these two-tier structure is not the proposed changes to Irish residency rules. That will have little impact. The big issue are the moves as part of the OECD’s BEPS project to align profits with substance, particularly employment. At the moment many of the (particularly US) MNCs operating in Ireland have their profit-generating IP assets located in Caribbean Islands where they have little more than brass-plate operations. If the BEPS proposals come to fruition the ability of companies to declare profits in locations where they have little or no real substance will be reduced. In the case of IP, substance will be judged on the basis of DEMP – developing, enhancing, maintaining or protecting the IP assets.

In this instance the companies will have a couple of options:

- First, they could move their staff involved in the DEMP of their IP assets to these Caribbean Islands to continue to avail of the low tax rates. Given the lack of infrastructure in these locations this is unlikely.

- Second, the companies could move the assets to where their DEMP staff are currently located. For US companies, this is the US. If the 35 per cent federal corporate income tax rate remains moving the assets to the US is unlikely.

- Thirdly, the companies could move both the assets and some of the key DEMP staff to another country that makes itself attractive to both.

It is through this option that Ireland has a massive advantage that cannot be replicated by other countries – regardless of how attractive their patent box is. The advantage Ireland has is that the IP of many US MNCs is already vested in Irish-registered companies.

The MNCs do not want to be transferring their assets between companies as this could potentially trigger tax liabilities and administering the changes consumes significant time and resources. They will want to restructure in the most tax-efficient and straightforward manner possible. One of the ways to achieve this is to move the location of the IP assets but not to change the ownership of them.

It is also the case that for many US MNCs, these Irish-registered IP holding companies have entered cost-sharing agreements with the US parent to gain the rights to the MNCs IP. Keeping the IP in the same company means that the cost-sharing agreement can be continued. These agreements lead to R&D expenditures discussed above which will come from Ireland if the company relocates here (and possibly making the profits eligible for Ireland’s ‘knowledge development box’).

The changes announced to Ireland’s residency rules have a grandfathering period where they won’t apply to existing companies for a period of six years. Ostensibly this was done to allow companies the time to restructure their operations. In actuality this grandfathering period is to ensure that the companies don’t change anything – at least until Ireland’s ‘knowledge development box’ is in place. Six years gives more than enough time for the OECD and EU discussions on patent boxes to be concluded and allow Ireland the time to legislate for a “best in class” version.

The intention is that US MNCs will keep their IP with Irish-registered companies (and the lead-in period to the end of the year is probably with the hope that a few more companies might do so). And the further hope is that if the BEPS proposals come to fruition the companies will choose option 3 and move their IP assets and some key IP staff to Ireland. Lots of “hope” and lots of “maybes”. The benefits may be massive or they may be nil.

How do we get US MNCs to choose option 3 and to do so in Ireland? First, the tax in the ‘knowledge development box’ has to be attractive enough so that it is not worthwhile to transfer the assets out of their Irish-registered companies. A tax rate of around five per cent should achieve that. It will be pretty easy to relocate the Irish-registered companies to Ireland as they are only brass-plate operations so a few board meetings with appropriate decision-making agendas will achieve that.

Next, we need the MNCs to move some key staff associated with their IP to Ireland (assuming they are not here to begin with). This may not be as straightforward. Dublin is not London or Paris. Ireland’s Income Tax regime is very different to our Corporation Tax regime. Schemes like the Special Assignee Relief Programme (SARP) can help but are not well-received. It is just one piece of a big jigsaw and there are just too many pieces that make explaining where it fits in very difficult.

Getting the necessary IP staff here will not be easy. Ireland does not have a wide or deep pool of high-quality researchers so focusing on the D and E (develop and enhance) of DEMP is unlikely to lead to much. Maybe we can achieve something on the M and P (maintain and protect) but it is not clear than any progress is being made in that direction. At present we just exploit the IP and more is required to satisfy the proposed OECD criteria.

All we can say at this stage is that the ground is moving quickly. Ireland has a significant head start over similar countries trying to gain in the area of FDI. The outcome may be beneficial but there is no guarantee of that. We may find the ground moving out from under us and where will we end up is difficult to project. With so many moving parts prediction is close to impossible.

The focus now is on intangibles, substance, DEMP, patent boxes and the like. That is where the game is. However, the purpose of Ireland’s Corporation Tax regime is to generate employment and maximise overall tax revenue. Just because the focus is on intangibles does not mean that is where our focus should be. The underlying primary objective has to be employment and there may not be many jobs in managing intangibles.

The tax profession will argue for a ‘knowledge development box’ because there will be plenty of work for them in that. The changes to our Corporation Tax regime over the next few years have to be about more than on-shoring low-tax outcomes.