The ongoing economic crisis facing the country has brought much commentary from home and abroad. One of the more significant contributions came last week from European Commissioner for Economic and Monetary Affairs, Olli Rehn. In a press conference he said:

“It is a fact of life that Ireland will no longer be a low-tax economy over the next ten years after what has happened.

I do not rule out any option since we know that Ireland in the coming decade will not be a low tax country, but it will rather become a normal tax country in the European context.”

These comments have attracted lots of attention, with much of the focus on Ireland’s 12.5% rate of Corporation Tax. The first issue to be addressed is whether Ireland actually is a low-tax economy. The weighted average tax-to-GDP ratio across the 27 members of the eurozone is 44.9% of GDP.

The usual source for tax revenue in Ireland is the Exchequer Returns. For 2009 these tell us that the Exchequer collected €33.0 billion in tax. We can get our GDP figures from the CSO. According to them GDP in current market prices in 2009 was €159.6 billion. Using these two figures gives a tax-to-GDP ratio of 20.7% – less than half of the EU average. This suggests that if our taxes were at the EU average of 44.9% rate tax revenue would be €71.6 billion. This potential extra tax revenue of €38.6 billion would eliminate an budgetary crisis.

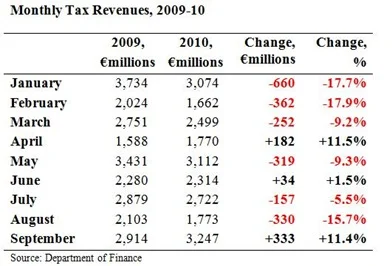

However, there are a number of major problems with this simplified analysis. The primary problem is that Exchequer Revenue does not equate to tax revenue. The Exchequer collects tax under eight tax headings (2009 receipts in brackets).

- Income Tax (€11.8 billion)

- Value Added Tax (€10.7 billion)

- Excise Duty (€4.7 billion)

- Corporation Tax (€3.9 billion)

- Stamp Duty (€0.9 billion)

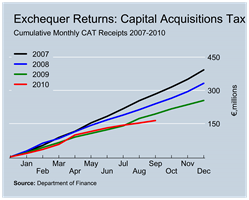

- Capital Gains Tax (€0.5 billion)

- Capital Acquisitions Tax (€0.3 billion)

- Customs Duty (€0.2 billion)

The sum of these gives the €33.0 billion collected by the Exchequer in 2009. Ireland, however, has numerous taxes that are not collected by the Exchequer that must be included in a measure of the total tax take. These figures are available from the CSO’s National Income and Expenditure Results. Some of these are (with 2009 receipts in brackets).

- PRSI Contributions (€8.9 billion)

- Rates (€1.4 billion)

- Motor Tax (€1.1 billion)

- Broadcasting Licence Fee (€24 million)

The existence of these taxes means that the tax take in Ireland in substantially higher than suggested by a glance at the Exchequer Returns. The EU Commission is well aware of these taxes and includes them in it’s measure of the tax burden in Ireland. The official eurostat figure for the tax-to-GDP ratio in Ireland for 2009 is 34.1%. With eurostat also reporting an 2009 Irish GDP figure of €159.6 billion, this means the total tax take in Ireland in 2009 was €54.4, over €20 billion more than the Exchequer tax receipts.

A tax-to-GDP ratio of 34.1% still puts Ireland well below the EU average of 44.9% and does little to belie the view that Ireland is a low-tax economy. Here are the Irish and EU rates for the past decade.

The next issue to consider is the burden of tax on Irish residents. For most of the EU the distinction between GDP and GNP is of little significance. Figures from eurostat reveal that for the EU27, the aggregate GDP of the EU was €11,787,279 million (€11.8 trillion). Separately eurostat reports that the aggregate Gross National Income (GNI, which bar a minor adjustment is the equivalent of GNP) was €11,748,223 million (€11.7 trillion).

Across the EU as a whole the GNI-to-GDP ratio is 99.7% – both measures of national income are essentially the same. The is not the case with Ireland. There is a substantial difference between GDP and GNI in Ireland because of the substantial outflow of profits by multinational firms. These profits form part of Irish GDP as they are based on economic activity in Ireland, but they do not form part of GNI, as the income does not accrue to Irish residents.

Using eurostat’s figures for 2009 the Irish GNI-to-GDP ratio for 2009 was 83.1%. This is a clear outlier. Nearly 17% of “National Income” flows out of the country and because it is taxed at a low rate it can distort the view of the tax burden on Irish residents. Using the GNI figures available the next lowest ratio is Portugal’s at 96.6%.

For most countries the tax-to-GDP ratio and the tax-to-GNI ratio are very similar. The one outlier is Ireland. Across the EU, the average tax-to-GNI ratio is 44.5%, not much different from the tax-to-GDP ratio of 43.9%.

Across the EU, Ireland (34.1%) has the fourth lowest tax-to-GDP ratio and is substantially below the EU average. Only Latvia (34.0%), Romania (32.1%) and Slovakia (34.0%) have lower ratios. In terms of tax-to-GNI Ireland comes 13th of the 27 EU members. Ireland is pretty much the median EU tax-to-GNI ratio. For Ireland that tax-to-GNI ratio in 2009 was 41.0%, pretty close to the EU average of 44.5%. This does not suggest that Ireland is a low-tax economy but is closer to a “normal tax economy” referred to by Rehn. Here is the tax-to-GNI ratio for Ireland for the past decade.

The amount of tax paid in Ireland as a proportion of the income of Irish residents is only slightly below the EU average. Of course, the total tax take is bolstered by the tax collected on multinational profits before they are repatriated. As we know these profits (and all business profits) are taxed at 12.5% and this rate is unlikely to be increased. If additional tax is to be collected it will have to come from Irish residents.

Those countries which had a lower tax-to-GNI ratio in 2009 than Ireland were Bulgaria (36.9%), Cyprus (40.3%), Czech Republic (40.3%), Greece (37.9%), Latvia (31.5%), Lithuania (33.9%), Malta (40.5%), Poland (37.4%), Romania (32.1%), Slovakia (34.4%), Spain (34.7%) and the United Kingdom (39.6%).

The unique features of the Irish economy make these comparisons difficult. Due to the large number, and impact, of foreign multinationals in Ireland it is appropriate that Ireland’s tax-to-GDP ratio be below the EU average. However, when it comes to the tax-to-GNI ratio Ireland should be above the EU average. This is the reflect the tax paid by Irish residents on the income they earn (as measured by GNI), and the tax paid by foreign multinationals on the profits they repatriate from Ireland (that do not form part of GNI).

With a tax-to-GNI rate below the EU average it does suggest that we are undertaxed (41.0% versus 44.2%), but does not support the assertion that we are a low-tax economy. The tax-to-GDP ratio (34.1% versus EU average of 43.9%) supports this low-tax theory but may not be the most useful comparison for Ireland.

In my view, it is likely that the appropriate tax-to-GNI ratio for Ireland is around 46.0%. In 2009 this would have required an increase in tax revenue of about €6.6 billion to €61 billion. This would equate to a tax-to-GDP ratio of 38.2%.

Ireland’s tax revenue has fallen, as the tax base was too heavily weighted towards construction and property transaction taxes. Some adjustment is necessary but the premise that Ireland is a low-tax economy should not be the starting point.

The 2009 data used in this post are all taken from eurostat and are available below the fold