Back in early 2016 we used the available information for this post to assess Apple’s international structure as it was up to the end of 2014. We will briefly recap that but our main purpose here is to update the narrative to the changes Apple made from the start of 2015.

This chart from the previous post summarises Apple’s original international structure. The detail behind it is explained in that post.

At the top, the parent company Apple Inc., holds the company’s hugely valuable intellectual property including patents, trademarks, brands and trade secrets. Through a cost-sharing agreement an Irish-registered subsidiary, Apple Sales International, was granted the rights to use that intellectual property outside the Americas. This is by far the most important part of the structure.

If the price ASI for that license is close to its economic value (or as the OECD would argue reflective of the value-adding activities of each party) then most of the value will accrue to Apple Inc. and be subject to immediate taxation in the US. However, because of the cost-sharing agreement the price based by ASI is not based on the value of the license but on the amount of research undertaken by Apple Inc. The contributions to the R&D are based on the revenue generated by the markets each party has a license for. It is likely that ASI pays for about 60 per cent of the research undertaken by Apple Inc. This is a large sum running to several billion a year but small relative to the tens of billions of profit that having the license to use Apple’s IP outside the Americas can generate.

ASI was controlled by a US-based board of directors. For the markets it had the license for, ASI contracted with third-party manufacturers in China to make the products and entered sales agreements with Apple-controlled distribution and retail subsidiaries as well as some large customers. ASI collected the huge mark-up between the manufacturing fees and costs and the sales revenue and was left with a huge profit after the cost-sharing payment was made.

It is not clear how the sales of ASI were recorded or reported for balance and payments and national accounts purposes. The company was “stateless” though the entity to which the profit was to be attributed, the head office made up of the board of directors, was based in the US.

To carry-out its underlying activities ASI had a branch in Ireland that undertook the supply, chain, logistics, demand forecasting, administration and other activities involved in getting the products from the manufacturer in Chine to the sales markets. The US board paid a fee to the Irish branch for these activities and the taxable income in Ireland was based on this fee rather than the global profits earned by ASI.

In the initial post we considered what would happen if they global profits were attributed to Ireland. The estimate was that the tax bill could come to €13.85 billion.

This is a bit higher than the €13 billion figure paraded by the European Commission but only because 2013 and 2014 outcomes for ASI were not publicly available at the time. Using the figures from Table 1 of the Commission’s decision which show lower profits for ASI in the final two years than shown above would give the €13 billion figure (even though the Commission itself never publicly verified this and only included references to the €13 billion in press releases rather than the final decision).

Anyway, we know what happened. The Commission have argued that no profit-making substance could be found in the minutes of the meetings of the US-based board of directors of ASI and hence little or no profit could be attributed to the board. The minutes did set out what banks and funds ASI’s billions should be placed with so the interest income ASI earned on its cash pile was attributed to the board of directors.

But what of the billions made in getting products made in China for $200 and selling them around the world for $600? Even though the contracts behind these activities were signed on behalf of ASI by US-based personnel, the minutes of ASI’s board meetings did not record the details of the negotiations and contracts so, in the Commission’s eyes at least, that means that the profits could not be attributed to the ASI board.

So what activities in the company could the profit be attributed to? Well, the only other substance in ASI was the Irish branch so the Commission decision was for “full profit attribution” to the activities of the Irish branch. The Court of Justice of the European Union will get to decide if this is correct.

Anyway, this is raking over old ground. What we are interested in here is what Apple did next. We know Apple changed its structure from the first of January 2015. This is described in section 2.5.7 on page 42 of the Commission’s decision. This would be useful but bar telling us that the new structure came into operation on the first of January 2015 everything else is redacted.

Although the details of the new structure were not revealed it was still felt that Ireland was still central to the structure and maybe even more so with the revised structure. Many of the dramatic shifts that occurred in Ireland’s national accounts and balance of payments data were attributed to Apple but this was largely supposition – even if it was likely to be true.

Now we know it to be true. Back in November, in response to a leak facilitated by the International Consortium of Journalists, Apple issued a statement on its tax affairs. Some extracts:

“The changes Apple made to its corporate structure in 2015 were specially designed to preserve its tax payments to the United States, not to reduce its taxes anywhere else. No operations or investments were moved from Ireland.”There is plenty here that is significant. To start we are told that when Apple sells a product outside the US the “sales and distribution activity is executed” in Ireland. If the sales are executed here (even if they are to another Apple subsidiary) they must be recorded here.

“When Ireland changed its tax laws in 2015, we complied by changing the residency of our Irish subsidiaries and we informed Ireland, the European Commission and the United States. The changes we made did not reduce our tax payments in any country. In fact, our payments to Ireland increased significantly and over the last three years we’ve paid $1.5 billion in tax there — 7 percent of all corporate income taxes paid in that country. Our changes also ensured that our tax obligation to the United States was not reduced.”

“When a customer buys an Apple product outside the United States, the profit is first taxed in the country where the sale takes place. Then Apple pays taxes to Ireland, where Apple sales and distribution activity is executed by some of the 6,000 employees working there. Additional tax is then also due in the US when the earnings are repatriated.”

“When Ireland changed its tax laws in 2015, Apple made changes to its corporate structure to comply. Since then, all of Apple’s Irish operations have been conducted through Irish resident companies. Apple pays tax at Ireland’s statutory 12.5 percent.”

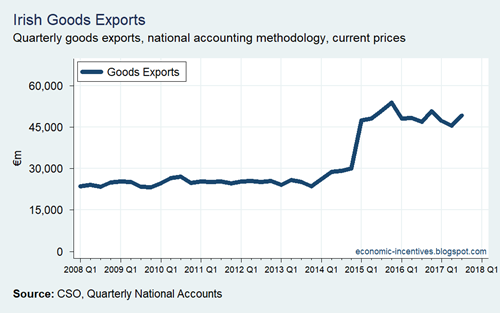

We know the products aren’t manufactured here so they won’t show up in the standard External Trade data. The products are made in China but are done so on behalf of an Irish-resident company. This is a form of “contract manufacturing” and even though the products are never physically in Ireland they are owned by an Irish-resident company and the sales of that company are included in broad measures of Irish exports. Here are Irish goods exports as recorded in the quarterly national accounts.

The level-shift in Q1 2015 is pretty clear with around €15 billion adding to quarterly goods exports. If these were goods made in Ireland we would know a huge amount about them but the additional exports do not appear in the External Trade statistics published by the CSO. This dataset better reflects the goods that physically leave Ireland (though the inclusion of aircraft on an ownership basis means that it is not absolute). Anyway, let’s compare goods exports as measured by the national accounting and external trade methodologies.

As expected almost all of the increase shows up in the gap between the two measures. The gap reflects a number of issues but one of them is “contract manufacturing”. Ireland did not suddenly start producing €15 billion a quarter of extra goods to sell from the start of 2015. What changed was where Apple’s sales were executed and recorded. This was previously with the head office of the non-Irish-resident ASI, but they have been recorded with an Irish-resident entity since the start of 2015. It is possible that this is Apple Distribution International, ADI, which took over many of ASI’s activities in 2012, except the contract manufacturing activity. This may have been added as part of the recent restructure.

The changed structure doesn’t change the profitability of the activity. Here is Table 1 from the Commission’s state aid decision.

For 2014, the final year prior to the restructure, ASI, which organised the contract manufacturing up to then, had revenue of around $68 billion and this led to a profit of around $25 billion. We can expect the outturns for the company which carried out this activity in 2015 to be similar.

And maybe we can see evidence of that in the national accounts’ aggregates published by the CSO and, in particular, the changes introduced between the preliminary estimates published with the Q4 2015 Quarterly National Accounts in March 2016 and the first annual estimates published a few months later with the 2015 National Income and Expenditure Accounts.

There can be lots of reasons for revisions to national accounts and it is likely that profits across a number of sectors were increased as more detail behind the 2015 surge in Corporation Tax receipts became known to the CSO. It is also the case that the differences shown are net outcomes between unseen amounts of various upwards and downwards changes. However, there is little doubt that one of the key additions for the 2015 NIE was the inclusion of Apple’s contract manufacturing activity for the first time and the recording of Apple’s product sales in the Irish accounts.

Looking at the changes to the expenditure components of national income.

- Investment was revised up by €6.8 billion. In national accounting R&D spending is considered investment (prior to ESA2010 it was intermediate consumption). The increase in investment in the NIE likely reflects inclusion of the cost-sharing payment for the R&D activity undertaken by Apple Inc. We know that ASI paid around $4.5 billion under the cost-sharing agreement in 2014 (see table six of the state aid decision) which was around 60 per cent of Apple’s overall R&D expense for the year. In 2015, Apple’s R&D expense increased by 25 per cent which would put the likely cost-sharing payment from the contract manufacturer in the realm of the increase to investment shown in the table above.

- Exports were revised up by €56.6 billion. In 2014, ASI had sales revenue of around $68 billion which in 2015 would give a ballpark for the sales now executed and recorded in Ireland.

- Imports were revised up by €20.2 billion. We don’t have a cost of sales figure to use but this would represent the manufacturing fee paid to the third-party manufacturer in China as well as the purchase of components from around the world for assembly in China. Although these goods could be shipped from other European countries to China they are counted as an Irish goods import as they are purchased by an Irish-resident company as part of a contract manufacturing arrangement. The assembler in China does not take ownership of the components.

Putting these expenditure items together leads to the upward revision in GDP. This was €41.2 billion which is a good deal more than the profits of ASI in 2014 which we are using as an indicative guide to the impact of the Apple restructure in 2015. As stated this likely reflects increased profits across a range of companies but something like $25 billion due to Apple cannot be discounted.

We would assume that most of these profits added in the NIE release would be the result of foreign-owned MNCs but we see that the net outflow of factor income was “only” revised up by €19.6 billion. This means that €21.6 billion of the additional income was counted as accruing to Irish residents.

We know Apple is foreign-owned so maybe the €19.6 billion represents the profits from Apple’s contract manufacturing being attributed back to Apple Inc. in the US. That would give a nice symmetry and completeness to the 2014 outturns for ASI and the changes introduced with the 2015 NIE for Ireland.

But as we’ll see our focus should be on the additional €21.6 billion attributed to the GNP of Irish residents rather than the €19.6 billion attributed to non-residents through increased net factor outflows.

To see this, we now turn our attention to the taxation of these profits. If the relocation of Apple’s contract manufacturing activities to Ireland led to an additional €19.6 billion of profits being attributed to non-residents it must be remembered that this is net profit, i.e. after taxation.

If €19.6 billion is after-tax profit, it implies that around €2.5 billion of Corporation Tax was paid. Now this actually could be in line with the large jump seen in Irish Corporation Tax receipts in 2015. So, did Apple pay a couple of billion of extra Corporation Tax in 2015? No. How do we know? The company told us.

In their recent statement Apple said in relation to Ireland that “over the last three years we’ve paid $1.5 billion in tax there”. So that is around $0.5 billion a year. A lot, yes, but not the scale we’re looking for.

Back when the state aid decision was announced, Luca Maestri, Apple’s chief financial officer said:

“In 2014, Apple paid in Ireland, to the Irish tax authorities, $400 million. $400 million in 2014. We believe, we're not certain, but we believe it's the largest tax payment that any company has made in Ireland.”From Table 1 of the state aid decision shown above we can see that this did not arise from the contract manufacturing activities undertaken by ASI in 2014 which declared a tax charge of less than $10 million. It is likely that the $400 million referenced by Maestri refers to other Apple activities in Ireland.

So, did Apple’s Corporation Tax payments in Ireland increase significantly after the 2015 restructure? No, it appears not. The payments do seem to have increased a bit but not significantly from what three times the $400 million payment for 2014 imply. This points to Apple not being a significant factor in the 2015 surge in Corporation Tax receipts. So, why didn’t the Apple restructure and the relocation of its hugely profitable contract manufacturing activities to Ireland lead to a jump in its Corporation Tax payments in Ireland?

May we should shift our attention away from the €19.6 billion increase in net factor outflows that the CSO included with the 2015 NIE and look instead at the €21.6 billion that was added to the estimate of Gross National Product. But why would tens of billions of profit from what is clearly a foreign-owned company be included in the GNP of Irish residents?

It is possible that the two questions that conclude the previous two paragraphs are related.

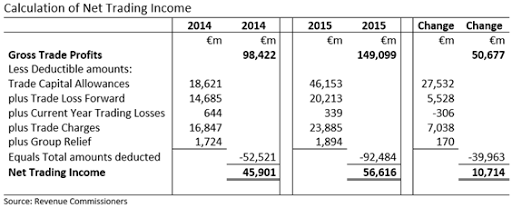

To explore this, we turn to data from the Revenue Commissioners and, in particular, the aggregate Corporation Tax calculation for 2014 and 2015.

We don’t have any revisions to help us here. Gross Trade Profits rose by €50.7 billion in 2015 but total amounts deducted increased by €40.0 billion so the increase in Net Trading Income was €10.7 billion.

Of the deductions, the most notable increase is the €27.5 billion increase in Trade Capital Allowances. Capital allowances are the tax equivalent of depreciation. When a company buys a capital item the expenditure on that item can be offset against profit and capital allowances spread that expenditure to be offset against gross trade profits over a number of years.

When the ICIJ reported on the latest data leak last November there was speculation that Apple was using capital allowances to offset the gross trading profits of its contract manufacturing activities which had relocated to Ireland in 2015.

The statement did not respond to speculation in this and other media outlets involved with the Paradise Papers project, that Apple has used Ireland’s capital allowances regime to avoid having to pay tax on massive profits being booked through Ireland.But if Apple had over €20 billion of additional profits in Ireland in 2015 with no noticeable increase in its tax payments then some offset mechanism was used to reduce the €2.5 billion of Corporation Tax payments that would typically ensue such profits.

In the “double irish” structure used by other companies such a reduction is achieved by outbound royalty payments. Some of these are shown as Trade Charges in the above table from the Revenue Commissioners but this excludes some which as classed as an administration fee and deducted “above the line” for the above table. The broadest coverage of these is in the royalties/license payments item in the Balance of Payments.

These did increase recently but almost all of that happened before 2015 and there is no level shift evident from the time of the Apple restructure in Q1 2015. Apple did not move to a “double irish” type structure with the 2015 restructure.

So that brings us back to the €27.5 billion increase in capital allowances in the Revenue statistics. The Revenue data is annual but it would be better to try and identify this increase in depreciation in quarterly data. Here is the consumption of fixed capital (the national accounting treatment of depreciation) for the non-financial corporate sector in the Institutional Sector Accounts.

We have a winner. There can be no doubting the level-shift that occurred in Q1 2015 with the depreciation of the non-financial corporate sector rising by over €6 billion at staying at the new elevated level.

Such a rise in depreciation can only occur if there is a significant increase in the stock of assets. If Apple is responsible then it would be the case that the license to use Apple’s intellectual property outside the US was relocated to Ireland. And, in order, for capital allowances to be claimed capital expenditure must be incurred.

Unfortunately, we don’t see direct evidence of such expenditure as it seems the company undertook the expenditure before becoming Irish resident, i.e., there was a balance-sheet relocation. But we can look for impact of the newly-Irish-resident companies on aggregate balance sheet data. If a company is going to acquire the license to Apple’s IP it may have had to borrow the money to fund the acquisition.

Ireland capital stock jumped by €300 billion in 2015 which was a 40 per cent increase in just one year. This was not new infrastructure (buildings, roads etc.) though data suppression by the CSO means we are left with a residual to be explained by transport equipment (including aircraft for leasing) and R&D assets. Figures for these two parts of the capital stock have not been provided since 2015 though their sum shows they were responsible for the jump in the capital stock.

Between them the stock of transport equipment and R&D assets increased by €260 billion in 2015. This increase does not show up in the capital formation data for that year for these were added to Ireland’s capital stock through balance-sheet relocations.

A typical second-hand wide-body aircraft might have a value of, say, €30 million. A thousand such aircraft would have a value of €30 billion. We cannot be certain but there is unlikely to have been 1,000 wide-body aircraft re-located to Ireland in 2015. Even if there was we are still left with an unexplained increase of €230 billion in Ireland’s capital stock. By process of elimination this is due to the relocation of intangible assets to Ireland, a large part of which is likely the relocation of the license for Apple’s IP outside the US to Ireland.

So this points to the use of capital allowances that have enabled Apple to keep their tax payments steady while relocating their contract manufacturing activity to Ireland with the subsequent execution and recording of their ex-US product sales in Ireland. But the company themselves haven’t said this is what they are doing. Or have they?

Consider this from the company’s 10-Q SEC filing from February 2017:

This relates to deferred tax assets linked to the internal transfer of non-inventory assets. Capital allowances are a form of deferred tax asset and the transfer/sale of a license from one subsidiary to another would be an intra-entity transfer covered by the new standards. Maybe Apple has loads of licenses to be transferring around but the rights to use the company’s intellectual property outside the US is as big as it gets.Income Taxes

In October 2016, the FASB issued ASU No. 2016-16, Income Taxes (Topic 740): Intra-Entity Transfers of Assets Other Than Inventory (“ASU 2016-16”), which requires the recognition of the income tax consequences of an intra-entity transfer of an asset, other than inventory, when the transfer occurs. The Company will adopt ASU 2016-16 in its first quarter of 2019 utilizing the modified retrospective adoption method. Currently, the Company anticipates recording up to $9 billion of net deferred tax assets on its Consolidated Balance Sheets. However, the ultimate impact of adopting ASU 2016-16 will depend on the balance of intellectual property transferred between its subsidiaries as of the adoption date. The Company will recognize incremental deferred income tax expense thereafter as these deferred tax assets are utilized.

Apple states that the income tax consequences of such transfers when it begins to recognise them in the first quarter of 2019 as a result of accounting standards changes that become effective at that time will be $9 billion. If this relates to the use of capital allowances in Ireland then we are looking at a minimum of $72 billion of capital allowances ($72 billion x 12.5% = $9 billion) being available at that time – and that is after tens of billions have been claimed each year since 2015.

We can see that impact these capital allowances have had on the company’s tax bill by looking at another dataset produced by the Revenue Commissioners. This is the aggregate tax calculation for companies with nil or negative net trading income. We previously looked at that in detail here.

We are primarily interested in the change from 2014 to 2015. For 2015, we see that companies with no net trading income had €40 billion of gross trading profits, an increase of €26.5 billion and a near trebling of the 2014 level. If Apple are responsible for a large part of the increases in capital allowances and depreciation we saw above then the capital allowances figure here is very revealing. For 2015, the amount of capital allowances available increased by €25.6 billion which one its own was almost enough to fully offset the increase in gross trading profits.

Net trading income feeds in taxable income on which Corporation Tax is levied. How much tax is due on net trading income amount of nil? Nil. The reason Apple’s tax bill didn’t increase in 2015 is because they were able to fully offset the gross profit from the contract manufacturing activity relocated to Ireland with capital allowances.

If should also be noted that such an outcome would not have been possible prior to 2015. Up to that time there was a cap on the amount capital allowances that could be used in a single year. This cap was set at 80 per cent of the income eligible to be offset by the capital allowances. So, if a company had, say, a profit of 20 and 25 of capital allowances available for that year the most that could be used in that year is 16 (80 per cent of 20) with the unused capital allowances carried forward to later years. For 2015 this cap was raised to 100 per cent so that all income could be offset provided sufficient capital allowances were available. See this note for a discussion.

Although it appears that Apple was able to fully offset the profit from the “contract manufacturing” activity in 2015 this may not be the case in future years if the level of profit rises above the annual amount of capital allowances available and, over a long enough period, continued profits will result in the capital allowances being fully exhausted at some stage with no further amounts available to deduct.

In their recent statement Apple said “[t]he changes we made did not reduce our tax payments in any country.” This is true for Ireland. Prior to 2015, Apple did not pay tax to Ireland for the contract manufacturing as it was not located here. When this activity was moved here in 2015 the amount of tax paid was also close to nil as the capital allowances wiped out the gross profits.

From an Irish perspective there isn’t anything hugely egregious about this. The Irish operations of US MNCs use technology and intellectual property that was almost exclusively developed in the US. That the Irish subsidiaries have to pay for the use of that technology is pretty standard.

In many cases this is achieved through royalty payments with the Irish company “renting” the license to use the technology. The expenditure on these outbound royalty payments reduce the taxable income in Ireland as they are incurred.

In more recent times we have seen Irish subsidiaries “buying” the license outright via IP onshoring. This once-off capital expenditure is also allowable as an offset to reduce a company’s taxable income with rules setting out how much can be claimed each year until the full amount is used.

Of course, in both cases these are payments for technology developed in the US so the payments should go to the US to reflect the value-adding activities that are carried out there. That the US allows companies to “offshore” their technology licenses for a cost-sharing payment based on the amount of research expenditure incurred rather than the amount of profit earned is a matter for the US.

But the European Commission has decided that what happens in Ireland is a matter for it. Back in November, Commissioner Vestager indicated she had some interest in what Apple did next:

“I have been asking for an update on the arrangement made by Apple, the recent way they have been organized, in order to get the feeling whether or not this is in accordance with our European rules but that remains to be seen”Page 42 of the state aid decision suggests that the Commission have all the information they need. Through an Irish lens the new arrangement does not pose concerns, from a tax perspective at any rate. An Irish company is exploiting technology developed elsewhere and has incurred capital expenditure buying a license for the right to use that IP - how much would you pay for the ex-US rights to Apple’s IP?

“We are looking into this of course without any kind of prejudice, just to get the information.”

The company didn’t pay much tax to Ireland on this activity in 2014 (because it happened somewhere else) and everything points to them not paying much tax to Ireland on it in 2015 (because the company in Ireland had to pay for the right to do it).

But what about through the lens of the European Commission? And in particular this subsection from the section of the Irish Taxes Consolidation Act (section 291A) that sets out how capital allowances for the acquisition of intangible assets can be claimed:

OK, while paragraph (a) means that a deduction of the capital expenditure incurred can only be taken once and paragraph (b) means that the amount to be deducted cannot exceed the arm’s length value, our interest is in paragraph (c): a claim for capital allowances for expenditure on intangible assets cannot be made as part of a tax avoidance scheme or to reduce a company’s tax liability. Let’s repeat some sentences from Apple’s recent statement:(7) This section shall not apply to capital expenditure incurred by a company—

(a) for which any relief or deduction under the Tax Acts may be given or allowed other than by virtue of this section,

(b) to the extent that the expenditure incurred on the provision of a specified intangible asset exceeds the amount which would have been paid or payable for the asset in a transaction between independent persons acting at arm’s length, or

(c) that is not made wholly and exclusively for bona fide commercial reasons and that was incurred as part of a scheme or arrangement of which the main purpose or one of the main purposes is the avoidance of, or reduction in, liability to tax.

“The changes Apple made to its corporate structure in 2015 were specially designed to preserve its tax payments to the United States, not to reduce its taxes anywhere else.”

“The changes we made did not reduce our tax payments in any country.”

“There was no tax benefit for Apple from this change and, importantly, this did not reduce Apple’s tax payments or tax liability in any country.”

And, yes, the company did put the second of these extracts in bold. There are keen to state that the structure did not reduce their tax liability. The final extract is actually in reference to Apple’s decision to redomicile the company that holds (or at least held) its overseas cash to Jersey. That is pretty much a non-issue. US companies must pay US corporate income tax on passive income they earn from third parties (such as interest) in the period in which it is earned.

If Apple had made that company Irish resident they would have had to pay our 25 per cent Corporation Tax rate for non-trading income and then pay an additional ten per cent to reach the then US rate of 35 per cent. By domiciling in Jersey no tax is due in that jurisdiction but the full 35 per cent would have been due to the US in any event. The Jersey element of this is a non-story.

But back to what might become a story. How might the European Commission view Apple’s decision to shift the “contract manufacturing” activity to Ireland in 2015? If viewed through their lens could it be construed as tax avoidance? Absolutely.

The logic of the state-aid decision is that, up to 2014, Apple owes tax on the profits from its “contract manufacturing” activity to Ireland because the only substance the Commission could see that was able to generate those profits was in Ireland. The Commission could not see evidence that the US-based board of directors was responsible for the profits so all the profits were attributed to the activities in Ireland. Of the €13 billion figure suggested by the Commission around €2.5 billion will be due to profits earned in 2014.

In 2015, Apple carried out much the same functions in Ireland but now the sales were executed and recorded in Ireland and the license for the IP was onshored to Ireland. From the perspective of the Commission the tax liability on the profits went from €2.5 billion to nil. Is that reducing a tax liability?

Maybe 291a(7)(c) would be satisfied if the company that received the money for selling the IP license had paid capital gains tax. But that didn’t happen. And maybe you could argue that from an Irish perspective it is up to the jurisdiction where the IP originated to ensure that the appropriate CGT is charged.

But the IP left the US when the cost-sharing agreement was put in place way back in 1980 and right up to 2015 it was held by a stateless company and located nowhere. The CGT rate in nowhere is zero. And the Irish branches had the use of the IP up to 2014.

If the Commission’s €13 billion decision is upheld by the courts then Apple will owe €2.5 billion of Corporation Tax for the €20 billion of profit earned by ASI in 2014. In 2015, much the same profit was earned by a related company in Ireland which carried out much the same activity except it has paid a couple of hundred billion to buy the license for the IP underlying the activity.

Again, from an Irish perspective this isn’t a huge issue. The profit linked to the IP wasn’t here in 2014 so wasn’t taxed here. The IP was onshored in 2015, which resulted in the profit being located here as the GDP changes illustrate. The profit was generated by an asset now located here so the profit offset by the depreciation of that asset was included in Ireland’s GNP. The company earning that profit had bought a license giving it the right to use that IP and such a payment would typically be deductible for tax purposes. The appropriate Irish law was followed appropriately.

But if you are the European Commission and your view is that €2.5 billion of tax is due to Ireland for 2014 then what else could you say but that the use of capital allowances in 2015 against the same profit (albeit in a different company) had as one its main purposes the reduction in liability to tax. Through the Commission’s lens such a claim for capital allowances would not be allowed per S291a(7)(c) though as well as showing that there was a reduction in the tax liability they would also have to show that it was not a bona fide commercial transaction so it is far from clear that such a view would hold up under legal scrutiny.

This means that what is at stake when the original state-aid decision is finally decided by the courts may not just be the €13 billion plus interest for the period from 2004 to 2014 but possibly also €2.5 billion to €3 billion for every year since. There would be no basis to challenge the use of capital allowances in the 2015 restructure if the €13 billion ruling isn’t upheld.

One question that arises is why didn’t Apple move to a “double irish” arrangement in 2015. They could have done so. The company had to change its original structure in response to the restrictions on “stateless” companies that was due to come into effect at the start of 2015 but the provisions against “double irish” structures in non-treaty partner countries that came in at the same time were grandfathered for existing companies until the end of 2020, and it may also have been possible to find a treaty partner country in which such an arrangement could achieve similar tax outcomes. Possibilities along this line were provided here.

As Irish-registered companies before the grandfathering cut-off Apple could have availed of the provisions to allow the company holding the IP to become resident in a no-tax jurisdiction until the end of 2020. When the residency rules first began to change we thought that is what the company would do (see last paragraph).

Apple could have had an Irish operating company exploit their IP and executing the sales but get the money out of Ireland via a royalty payment to the IP holding company. The restructure needed to be put in place from the start of 2015 and the grandfathering would have given a six-year timeframe for a structure using, say, Bermuda.

Now, maybe the company didn’t want to go down the line of using a pure tax haven and they may also have believed there was a risk that the European Commission would examine “double irish” type structures as part of the ongoing state aid investigations. This is precisely what the Commission have done in the Amazon-Luxembourg case – see discussion here – and it is possible that similar two-company arrangements in Ireland will be put under the microscope in due course. But it equally must have been the case, back in 2014 at any rate, that Apple’s expectation of a “full profit attribution” outcome to their state aid case must have been low.

Anyway, we are where we are. Apple onshored their IP to Ireland in 2015 and the consequences for the company and the country can be traced though various figures and statistics as we have done here. Since the restructure was put in place we have had the Commission’s announcement in August 2016 of their conclusions in the state aid case and the rapid progression of changes to the US tax code through Congress in late 2017. There are also a number of mooted changes to Irish Corporation Tax possibly coming down the tracks. It is highly likely we will have another Apple restructure to pick through in due course but until then what is at stake in the state aid court case will potentially be getting larger and larger.

That's interesting, you have done a great job. Thanks for sharing.

ReplyDeletepmt

unfired pressure vessel

non destructive testing services in malaysia

If anyone’s looking for expert help with sales tax, check out this firm – Sales Tax Recovery | Sales and Use Tax Recovery

ReplyDeleteGreat article with interesting information. Hope you keep up with such a great work.

ReplyDeletedata erasure

data sanitisation

refurbished laptop malaysia

Amazing insights on Apple’s latest moves! Businesses looking to enhance their web and app interfaces can greatly benefit if they Hire Frontend Developers . Leveraging skilled developers ensures a smooth, modern, and engaging user experience for all platforms.

ReplyDelete