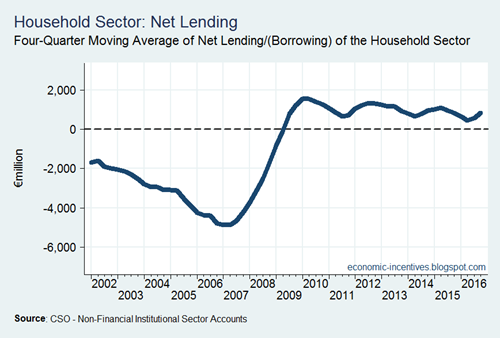

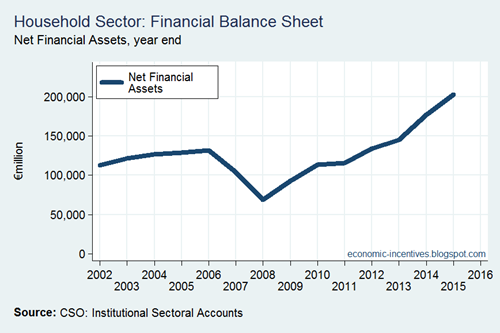

After the previous post’s trawl through the household sector accounts, here we have a look at the non-financial corporate sector in the Q4 Institutional Sector Accounts released last week. Of course, whatever caveats there are about revisions are even more pronounced for the NFC sector but there is likely to be value in the data, particularly if we can gain some insight into what is happening in the domestic business sector (by assuming that revisions are more likely from the MNC side).

First, the current account:

We should immediately be drawn to the 21.3 per cent rise in Gross National Income in 2016. Working through the numbers we can try to see what the source of this increase was.

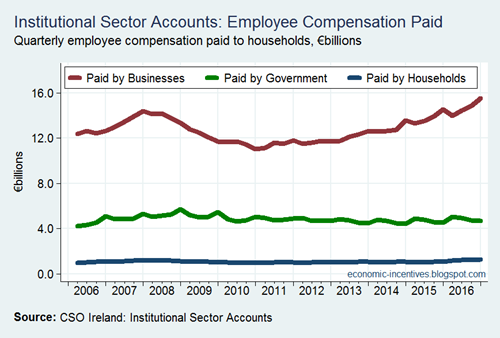

It doesn’t appear to be increased output or profits. Gross Domestic Product (i.e. value added) of the NFC sector grew by 3.8 per cent in 2016 and with COE paid growing by double that amount at 7.5 per cent there was “only” a 2.2 per cent rise in Gross Operating Surplus (akin to EBITDA).

So if profits are up two per cent how is Gross National Income of the NFC sector up more than 20 per cent? It may be down to who is earning those profits. It is a well-worn path but we know that the net profits of foreign-MNC subsidiaries operating in Ireland are rightly attributed to their foreign parents. This can be explicitly through the payment of dividends or implicitly through the attribution of any retained earnings to the foreign parent. The split doesn’t really matter. Their sum gives us an indication of net MNC profits earned in Ireland.

In 2015, dividends paid and retained earnings owed by the NFC sector summed to €57.7 billion. For 2016, it is estimated that these summed to €49.9 billion, a drop of almost €8 billion. So while NFC profits may have increased by €3 billion it appears that the performance of domestic companies was much stronger as MNC profits appear to have fallen by €8 billion.

Increased profits and reduced factor outflows explain most of the increase in GNI (accounting for €11 billion of the €14 billion increase). The remainder is explained by increased factor inflows.

It can be seen that retained earnings owed to Irish-resident NFCs grew by more than 40 per cent in 2016, a rise of nearly €4 billion. Although these could be the foreign-source profits of Irish MNCs most of the changes in the item have recently being driven by the foreign profits of companies which have redomiciled their headquarters to Ireland. It is clear that these companies had a good 2016 but these profits bring no benefit to Ireland.

And we have one further caveat to explore before coming down strong that the performance of domestic companies was strong in 2016: depreciation. The above table gives gross measures. It will be the case that some of this gross income will be absorbed by depreciation. If there has been an increase in the amount of depreciation attributed to the Irish assets of foreign-owned companies then the changes in gross income will not be reflective of changes in domestic businesses. We can try and get some insight from this in the capital account.

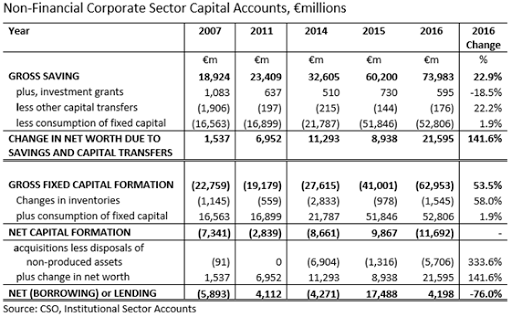

There is a good bit going on but our focus is on “consumption of fixed capital”. We can see that this was relatively stable in 2016, showing growth of just 1.9 per cent. This is in marked contrast to what happened in 2015 as shown below.

The dramatic rise in depreciation is obviously related to mobile assets. The two candidates are aircraft and intangibles. The scale of the increase in the capital stock means intangibles are the culprit. This is the onshoring of intangibles by MNCs. A transaction involving c.€24 billion of intangibles occurred in Q4 2016 (as reflected in the quarterly national accounts described here) but the impact this had on depreciation was small relative to the hundreds of billions of intangibles that were on-shored in early 2015.

The acquisition of these assets will enable the companies to avail of capital allowances to offset the capital expenditure incurred against their trading profits. Although the Revenue Commissioners have not yet published the aggregate Corporation Tax statistics for 2015 we can expect that they will show an increase in the capital allowances used by companies of something approaching €30 billion.

In 2015, the Gross Operating Surplus of the NFC sector increased by €53 billion. The amount of Corporation Tax paid by the NFC sector increased by €1.8 billion. This suggests an increase in Taxable Income of around €20 billion. The reason a large part of the increased Gross Trading Profits did not translate into Net Taxable Income was because of the use of Capital Allowances. If Capital Allowances were not available then one could surmise that CT receipts would have been around €2.5 billion higher again. However, if the Capital Allowances were not available then the IP would not have come here in the first place.

And it is also because of Capital Allowances that the distinction between gross and net profits in the NFC sector is important and why we have to be careful about drawing implications about the domestic sector from gross measures.

Still, the three pieces of evidence we have point us in the direction of a strong performance of domestic enterprises in 2016:

- the sum of outbound dividends paid and retained earnings fell by €8 billion;

- depreciation was relatively stable increasing by just €1 billion;

- retained earnings of re-domiciled PLCs accounted for a little over a quarter of the rise in Gross National Income

It is these muddying features it is hoped that the proposed GNI* will throw some transparency on to allow us to see what is happening the domestic economy. As we said before:

In rough terms GNI* will be the standard “GDP less net factor income from abroad” to get to GNP with the (positive) balance of EU taxes and subsidies used to get to GNI. After that, additional adjustments will be made for the depreciation of intangibles that MNCs have located here and the net income earned by redomiciled PLCs. With these adjustments we should get a better measure of aggregate income developments for Irish residents.

When the Q4 QNAs were released we suggested that:

It’s little more than a guess but, assuming some fall in MNC profits last year, a growth rate in 2016 for GNI* of somewhere around 6 to 7 per cent may not be too wide of the mark.

There was nothing in the institutional sector accounts to contradict that conclusion. As shown here the evidence supports it.

Tweet