One of the notable features of the distribution of income in Ireland in the decade after the crash of 2008 was the unusually high level of inequality of market income. See this previous post for some discussion of definitions.

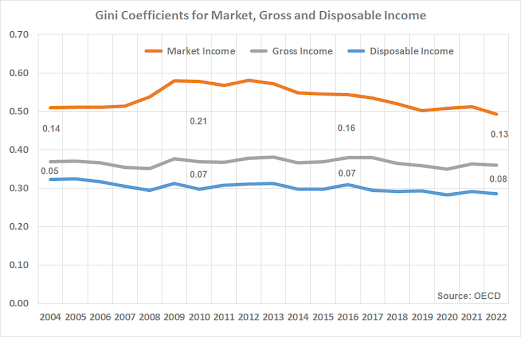

Using estimates from the OECD, the gini coefficient for the distribution of market income reached almost 0.60 in the years after 2008 and was the highest in the OECD (and also the EU). However, since then the gini coefficient for market income has declined and the latest update from the OECD shows the estimate falling below 0.50 for the first time.

The distances between the ginis are indicative of the impact of transfers on income inequality (from market income to gross income) and of taxes (from gross income to disposable income).

The impact of transfers rose considerably in the crash, as 300,000 jobs were lost and many became reliant on unemployment-related and other transfers. With the onset of the recovery, the impact of transfer reduced as the numbers working rose with a related fall in the numbers on unemployment supports.

Using OECD estimates for 2010, it can be seen from the difference between the gini coefficient for market income and for that for gross income, that transfers reduced the gini coefficient by 0.21 points. By 2016, this had fallen to 0.16 with a further reduction to 0.13 in 2022 which is the lowest it has been put at in the series.

On the other hand, looking at the difference between the gini coefficient for gross income and that disposable income, the impact of taxes on income inequality is estimated to have increased in the past 20 years, from 0.05 points in 2004 to 0.08 at the latest estimate.

Here is where the estimate of the gini coefficient of market income for Ireland sits relative to the 41 other members of the OECD.

It can be discerned how much of outlier an estimate close to 0.60 would be. But the latest estimate for Ireland below 0.50 moves Ireland relative position towards the middle of the OECD ranking. Ireland is now 13th of the 42 OECD member states and converging on the arithmetic average for the OECD of 0.47.

Ireland remains below the OECD average for the gini coefficient of disposable income with a 2022 estimate of 0.29 compared to an OECD average of 0.32. This means the impact of transfers and taxes in Ireland remains high in EU terms, with their combined impact the fourth highest in the OECD (and also in the EU).

The impact of transfers on the gini coefficient in Ireland is now close to the OECD average, 0.13 in Ireland versus an arithmetic average of 0.12 across the OECD. It is for the impact of taxes that Ireland continues to stand out.

In 2022, Ireland’s gini coefficient for disposable income was 0.075 points lower than that for gross income. No other country showed a reduction in inequality due to income taxes and social contributions as large as this.

Finally, given the impact of demographics, old-age dependency ratios and pensions, here is the gini coefficient for market income for those who are most likely to be in receipt of it – the working age population from 18 to 65 years.

Ireland is eighth-highest in the OECD, though the gap to the OECD average is modest. Among EU member states, only France and Greece have higher estimates but is within a couple points of five or six more.

The CSO use a slightly different definition of market income (and also report gini coefficients as percentages) and their latest estimates from the 2024 SILC (which will be used for 2023 by the OECD) point to a further recent reduction in the gini coefficient for market income.

If this reduction is reflected in due course in the OECD estimates then Ireland’s gini coefficient for market income may very well have moved to OECD average.

Tweet