One feature of how the inequality of disposable income is determined in Ireland has been the recent decline the in the inequality of market income. Market income is typically defined as including wages, rents, dividends, interest and typically certain pension income such as from private and occupational pensions.

Here is the OECD’s estimate of the gini coefficient for market income in Ireland since 2012 (chart crime incoming):

In the OECD’s dataset, the figure for the latest year, 2021, corresponds to the household survey undertaken for SILC2022. The reference year for income in the SILC is now the previous calendar year and this is the year the OECD use in their database. The 2022 outturn for Ireland will be based on the survey done for SILC2023. It should also be noted that in SILC2023 the CSO revised their SILC results for 2020 to 2022 (due to the population findings of the Census) though the impact of the revision on the main measures of income inequality was modest.

The recent reduction in Ireland of the inequality of market means Ireland no longer has the highest gini coefficient for market income in the OECD. The latest estimates show that France, Italy, Finland and the U.S. among others have higher gini coefficients for market income, with Ireland eighth highest.

It should also be noted that although the inequality of market income has been declining in Ireland for the past decade it has been lower previously – with lower gini coefficients estimated for the late 1990s/early 2000s.

The chart below has the recent outturns for Ireland and a selected set of OECD countries, showing Ireland losing its outlier status (and is also a chart having the vertical axis more appropriately start at zero).

We can start to get some insight into the nature of the fall in the inequality of market income in Ireland by looking at income shares. These can be determined using the information in the ESRI’s PILSReP Database.

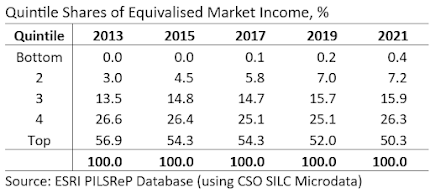

Here are the quintile shares in the SILCs for selected years since 2013:

It can be seen that the market income share of the top 20 percent declined from 57 percent in 2013 to 50 percent in 2021. The offsetting share increase can be seen for the bottom three quintiles. The share of market income going to the bottom 60 percent increased from 16.5 percent in 2013 to 23.4 percent in 2019.

We can get more granular detail on this change by looking at the Lorenz curves – a plot of cumulative shares by the cumulative population. Here are the Lorenz curves for the distribution of market income in the 2013 and 2021 SILCs (again using figures from the ESRI’s PILSReP spreadsheet):

The most significant change happened at the bottom where there was a large reduction in the number of zeroes (i.e. non-recipients of market income). In the 2013 distribution of market income, a cumulative share of one percent was not reached until the 33rd percentile. By 2021, this was reached by the 24th percentile (with the 33rd percentile having a cumulative share of 4.1 percent).

The 2013 Lorenz curve remained at zero until the 22nd percentile; the 2021 distribution was zero until the 13th percentile. The recovery and expansion of employment significantly reduced the number of zeroes in the distribution of market income.

The associated reduction in unemployment also means that the impact of transfers on income inequality has also fallen. We can see this if we return to OECD data and look at their gini coefficients for market income, gross income (market income plus transfers) and disposable income (gross income minus taxes and social contributions).

For 2012, the OECD put the impact of transfers on Ireland’s gini coefficient at 0.20 points, reducing the gini coefficient from 0.58 for market income to 0.38 for gross income. The impact of taxes further reduced the gini coefficient by 0.07 points, giving the gini coefficient of 0.31 for disposable income.

For 2021, the impact of transfers reduced to 0.15 points (due to there being fewer recipients of unemployment related transfers). Transfers reduced the gini coefficient for market income from 0.51 to 0.36 for gross income. The impact of taxes was largely unchanged again reducing the gini coefficient by 0.07 points, giving the gini coefficient for disposable income of 0.29.

Thus, while there was a reduction of .07 in the gini coefficient for market income, this translated into a reduction of “only” 0.02 in the gini coefficient for disposable income, due to the reduced impact of transfers.

We can use the OECD to examine the impact of transfers and taxes on income inequality in all OECD member states in 2021 (or the latest available year in the dataset).

For 2021, the combined impact in Ireland of transfers and taxes on income inequality was the fourth highest among OECD countries. For transfers, Ireland was eighth highest, with transfers in Finland, France, Greece, Belgium, Austria, Poland, Italy and Czechia all having a bigger impact on inequality.

For taxes and social contributions, Ireland continues to stand out, with the 0.07 point reduction in Ireland having the largest impact on income inequality in the OECD.

Eurostat also provide measures of market income inequality. One of these is an S80/S20 quintile share ratio for gross market income. The outturns of this quintile share ratio for Ireland have shown a remarkable reduction in recent years; falling from almost 100 in 2013 to around 15 now.

The huge swings in this measure, at least for Ireland, indicate that it is sensitive to small changes at the bottom of the distribution. It was the relatively high number of zeroes in the distribution of market income in Ireland that gave rise to the exceptionally high outturns up to 2013 for this measure.

One can imagine the top 20 per cent/bottom 20 percent ratio being something like 50/0.5 in 2013 (giving an answer of c.100) and this moving to something like 50/3.5 in recent years (giving an answer of c.15).

This is a relatively small change in the share of the bottom 20 percent (from 0.5 percent to 3.5 percent) but it has a marked impact on the outturn for the quintile share ratio. And even with this reduction, Ireland remains the highest in the EU for this measure.

We could calculate a similar quintile share ratio using the shares of market income from the ESRI estimates in the table provided earlier. But the answer would be very very different, i.e. over 100 for recent years (50.3/0.4 = 127, for 2022), rather than the 15 shown in the Eurostat results for 2022.

The reason for the difference is due to the income definitions used. The CSO (and the OECD) only include private and occupational pensions in their measure of market income. For their measure of gross market income, Eurostat include all old-age transfer payments. This includes state pension benefits such as means-tested and non-contributory pension benefits and all survivors pension benefits. This is based on the concept of pension income being a part of lifetime earnings. Outside of private and occupation pensions, the CSO (and the OECD) count pension income as a social transfer, i.e., not part of market income.

Ireland’s gross market income quintile share ratio is high because of the relatively high number of non-recipients of market income and the relatively low number of pensioners. It has been found that excluding zeroes, Ireland “lies around mid-table in terms of market income inequality” in the EU.

It is also the case the estimates of market income inequality have tracked the estimates of quasi-jobless households (households with very-low work intensity where less than one-fifth of the available time is worked). For a considerable period, Ireland had the highest share in the EU for population aged under 60 living in households with very-low work intensity. This has not been the case since 2018. The lower level of quasi-jobless households is linked to the lower level of market income inequality – both are estimated using the SILC.

Eurostat also provide a number of gini coefficients. All of these are after income taxes and social contributions have been deducted but then vary in the amount of social transfers that are included. Eurostat provide three gini-coefficients:

- Disposable income before all social transfers

- Disposable income including pension transfers

- Disposable income including all transfers

The final one is just the standard disposable income while the first is akin to market income after taxes. Here are the estimated gini coefficients across the EU15 for disposable income before all social transfers:

By this measure of market income inequality, Ireland has had, in recent years, one of the lowest levels in the EU15. This is after taxes and social contributions have been deducted and again we note that in Ireland these have the biggest impact on the gini coefficient across both the OECD and EU.

Taxes alone are unlikely to account for Ireland’s relative position here, which is at odds to what we have seen for other measures of market income inequality, such as the quintile share ratio. The difference in results suggests the definitions used are important. The quintile share ratio is determined using gross market income.

As discussed above this includes all pension income. The previous chart excludes all pension income. This would suggest that pension income has a significant impact on Ireland’s relative position using the quintile share ratio for gross market income.

We can see this if we look at the gini coefficient after adding in pension income.

So, after taxes and before all transfers, Ireland has a relatively low gini coefficient across the EU15. Once pensions are added in, Ireland has one of the highest gini coefficients in the EU15 (with the higher UK estimate in the above chart going back to 2018 when the UK last provided data to Eurostat). Eurostat quintile share ratio for gross market income includes all pension income which may go some way to explaining Ireland’s relatively high outturn for that measure (due to Ireland having a lower old-age dependency ratio).

This highlights that the impact of pensions is key to the transition from the distribution of market income across the population to that of disposable income. We don’t get much insight into this from the OECD’s income inequality estimates.

However, we can examine it if we look at the three gini coefficients provided by Eurostat at the same time. Here they are for Ireland since 2012:

In line with earlier results we see a decline in the gini coefficients from Eurostat for those income measures most closer aligned with market income. The gini coefficient for disposable income before all transfers declined from 53.5 in 2012 (Eurostat uses the 0-100 scale) to 47.0 in 2022. The gini coefficient for disposable income including pension transfers declined from 46.1 in 2012 to 38.6 in 2022.

The difference between those gini coefficients reflects the impact of pension transfers on income inequality. We can see that this has increased over the past decade, from an impact of 7.4 in 2012 t0 one of 8.5 in 2022. This is likely explained by the increasing share of pensioners in the Irish population.

The final gini coefficient is that for disposable income. This has also declined, albeit more modestly, from 30.4 in 2012 to 27.9 in 2022. The different to this gini gives the impact on income inequality of all transfers other than pensions. We can see that this has declined from 15.7 in 2012 to 10.6 in 2022. Again, this is likely driven by the reduction in unemployment and the reduced need for unemployment-related income supports.

We can compare the impact of pensions and other transfers across the EU in 2022.

In line with the OECD estimates, the estimates from Eurostat show that Ireland does not stand out for the impact of transfers on income inequality. In 2022, the impact of transfers on income inequality in Ireland was the ninth highest in the EU27.

However, what the Eurostat estimates allow us to see is the composition of that impact which can be broken down into that due to pensions and that due to transfers other than pensions.

And using this we can see that the impact of pensions on income inequality in Ireland is the lowest in the EU27, due likely to the low share of pensioners in Ireland’s population and also possibly the flat-rated benefits under the State pension schemes. And, on the other the impact on income inequality of transfers other than pensions in Ireland is the highest in the EU27. This will mainly reflect the impact of working-age transfer payments.

And, all of this is just how we get to the bottom line: disposable income. This is the income people have available to spend. The rest are somewhat notional figures. So, to conclude here are the gini coefficients for disposable income across the EU15.

In terms of the EU15, Ireland has moved from upper-middle to lower-middle for the inequality of disposable income.

No comments:

Post a Comment