An article by Donal Donovan in last Saturday’s Irish Times reiterates a point made previously that the almost-blanket two-year guarantee introduced for the six Irish banks in September 2008 was the “least-worst option”.

Careful examination of all the possibilities available at the time leads one to conclude, as did the Honohan and Nyberg reports (and my recent book jointly authored with Antoin Murphy), that some form of comprehensive guarantee could not have been avoided – it was the least worst alternative.

I think a careful reading of the Honohan and Nyberg reports is that once all other alternatives had been eliminated the only remaining option was a comprehensive guarantee. Much of their respective discussions focus on the reasoning, or lack thereof, that led to the exclusion of possible alternatives.

What were the alternatives? We previously looked at some of these around the time of the first ‘Anglo Tapes’. Combining the reports of Honohan and Nyberg with the note from Merrill Lynch given to the government on the night of the guarantee provides the following list:

- Guarantee of all existing liabilities (blanket)

- Guarantee of some existing liabilities (partial)

- Guarantee of new liabilities

- Put failed banks into resolution/liquidation

- Consolidation of banks through mergers

- Nationalisation of distressed banks

- Put distressed banks into protective custody through preference shares

- Split distressed banks into good banks/bad banks

- Offer immediate liquidity through a Secured Lending Scheme (SLS)

- Offer immediate liquidity through Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA)

Some consideration was given to most of these but the latter nine were eliminated for one reason or another. The Merrill Lynch report at the time and the Honohan and Nyberg reports in retrospect all favoured the immediate provision of liquidity to the banks who needed it. Merrill Lynch began the conclusion of their report with:

The extension of a discreet liquidity advance is important to stabilise Anglo [and possibly INBS] and avoid contagion risk.

However, it was decided that liquidity would not be provided from either the assets of the NTMA or the money-creating facilities at the Central Bank of Ireland. Here is Nyberg on this decision (paragraph 4.7.8):

The policy decision not to use such alternative funding seems to have been based on judgment rather than on an externally imposed limitation. Had the authorities or the Government wished to avoid immediately providing a broad guarantee, some of these funding options were available though, perhaps, not easily. Buying time, even until following week-end, would not have been an idle exercise. It would have allowed the authorities the opportunity to assess more extensively the advantages and disadvantages of the alternative approaches available. The issue of urgently scrutinising and possibly nationalising certain banks could have been considered, including the option of splitting off their bad assets into variously managed nonbank vehicles (for which funding would have had to be found). There would perhaps have been some scope for discussing and streamlining policy alternatives more intensively with euro area partners. In the best case scenario, there could have been sufficient time to allow for the emergence of an initial common EU approach to the crisis. High priority could even have been given to urgently pursuing legislation covering a special resolution regime, thereby expanding the options available for addressing the fallout from a potentially insolvent financial institution.

And similarly Honohan (paragraph 8.51):

In addition to influencing financial stability policy, a key role of the Central Bank in a crisis is to ensure adequate provision of liquidity. It was prepared on the night of 29/30 September to extend a modest amount of ELA, but not enough to ensure that Anglo would get through the week. Thus back-up liquidity provision was instead hastily secured from the two largest commercial banks, and, crucially, backed by Government guarantee. In effect, the commercial banks were stepping in to provide the lender of last resort facility – which of course was in their own interest to do. The reluctance to deploy more significant ELA facilities from the Central Bank is open to question: such facilities were being used elsewhere and too much was likely made of the reputational risks involved (especially given that the guarantee was about to be announced). It is unlikely that even extensive use of the facility to buy time to facilitate nationalisation the following weekend would have been viewed negatively by partner central banks under the circumstances. While use of ELA would only have been a temporary solution, it might have bought some breathing space while other possibilities were being explored to address the unprecedented situation that many – not only in Ireland – were facing.

So the decision not to provide immediate liquidity was a “judgement” that was “open to question”. Not exactly ringing endorsements of the path actually taken. It was the refusal to provide liquidity that made a guarantee all but inevitable. And as was discussed in the previous post Anglo did not look for the guarantee in September 2008; they just wanted liquidity to keep the doors open.

Of course, it is possible that providing liquidity would have made little difference to the final outcome but it should not be viewed through a lens of “there was no alternative”. Both Honohan and Nyberg allude to “buying time” or “breathing space”.

Although reference is made to possible solutions at EU level it is clear that none was envisaged by the government on the night the guarantee decision was made. In fact, in a Seanad debate on the emergency legislation for the guarantee that took place on the Wednesday morning, Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan said:

As far as Europe is concerned, and I am a strong European who is proud of our participation in the euro, we were on our own last Monday evening. People are complaining that only six institutions are covered by the proposed measure. The six institutions in question would have been orphans in the world if the sovereign Irish State had not supported them last Monday evening. All the other institutions which want recognition have other sovereigns behind them, some of which are much bigger and more powerful than this State. We had six institutions which had no one to turn to but the sovereign Irish State.

The timestamp on the transcript shows that this was said just before 5am. But a lack of European support on the night in question is not sufficient to justify the two-year guarantee enacted. It was too late in Ireland’s case as policy here became locked in because of the guarantee but the European response did come just 12 days later at an EU summit in Brussels. At this summit it was decided, among other things, that the central banks would provide liquidity to banks that needed it.

Ensuring appropriate liquidity conditions for financial institutions.

6) We welcome the recent decision by the European Central Bank and other Central Banks in the world to cut their interest rates.

7) We also welcome the decisions by the European Central Bank to improve the conditions for the refinancing of banks and to provide more longer term funding. We look forward to Central Banks considering all ways and means to react flexibly to the current market environment.

We welcome the intention of the ECB and the Eurosystem to react flexibly to the current market environment, in particular in considering to further improve its collateral framework with regard to the eligibility of commercial paper.

So if banks needed liquidity the ECB was prepared to relax its collateral rules and provide the liquidity through the ECB’s refinancing operations. If that failed, ELA through the national central bank remained an option. Although it happened much later, the case of the Cypriot banks has shown that the ECB will make liquidity available in almost all circumstances.

It must be remembered though that regardless of what was done the dye was set by the end of September 2008. The banks were bust and there was nothing that could have been done to prevent a hugely expensive banking crisis. However, any possible incremental cost of the guarantee should not be discounted because it is small relative to the overall fiscal cost of the banking crisis.

If the two-year near-blanket guarantee had not been implemented how much would have been saved? That is an impossible question to answer as it is not a case of reducing costs but of redistributing them, and different courses of action may result in higher or lower overall costs to be distributed.

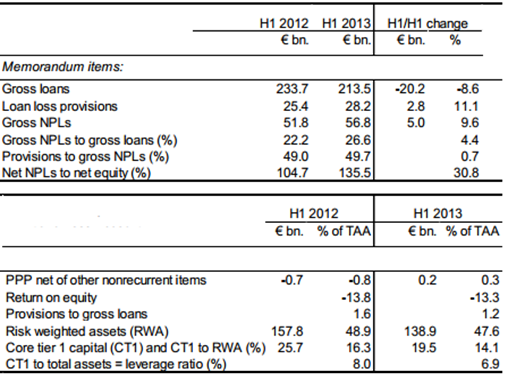

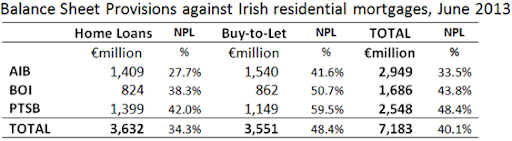

So far the State has provided €64 billion to our delinquent banks. The rescue, and associated costs, of AIB, BOI, EBS and PTSB were always going to be undertaken. The question is the rescue of Anglo and INBS which has an estimated cost of €35 billion. Patrick Honohan is clear that this should not have happened (albeit under the proviso of knowing what we know now) in footnote 18 of this speech.

It would have been better had Anglo and INBS been put into resolution as soon as it became clear that their capital was going to be wiped-out by unavoidable losses on developer loans. This should have been evident before September 2008, but was not, leading the Government of the day to include these two failed entities in its blanket guarantee.

Was it clear to anyone that Anglo and INBS were going to have their capital wiped out? Morgan Kelly said so in public and someone in the Department of Finance thought so in private. At a meeting that took place “about” the 25th September the then Secretary-General of the Department of Finance, David Doyle is recorded as noting:

“that Government would need a good idea of the potential loss exposures within Anglo and INBS - on some assumptions INBS could be €2 billion after capital and Anglo could be €8.5 billion.”

The ‘Anglo Tapes’ have also shown that Merrill Lynch were in favour of some form of shut-down of Anglo. This was said by Anglo CEO, David Drumm on the 15th of December 2008:

“It’s Merrill’s. And according to, erm, Alan Dukes today, the government ignored Merrill's advice and didn't shut us. You know, they wanted us nationalised. 'Just take them off the field, they're a basket case.' And ignored the advice and said: 'No. We want, we want to see if we can get the banks through this.”

It is not clear when or how this advice was given or if the proposal would have resulted in any reduction of the fiscal cost of the Anglo bailout. The point is merely to show that the solvency of the banks was been discussed and that they were some participants who were of the view that Anglo was beyond redemption. Of course, this was also the time that David Drumm was talking of a bond buyback in Anglo that he said would generate €9 billion in savings. It not clear how this would work or how it would fit in with the guarantee.

Merrill Lynch might have advised that Anglo was a “basket case” before December 2008 but two months later PwC presented a report to the Department of Finance which concluded that Anglo was sound and would continue to remain so:

“Under the PwC highest stress scenario, Anglo’s core equity and tier 1 ratios are projected to exceed regulatory minima (Tier 1 – 4%) at 30 September 2010 after taking account of operating profits and stressed impairments.”

It seems to have been a case that advice to cover all viewpoints was available and it was simply a matter of picking the one that best fitted the narrative one was trying to sell or the one that tied in with a policy that had become locked in.

The September 2008 guarantee did increase the fiscal cost of the banking crisis. On this the Honohan report (paragraph 8.39) says :

The scope of the Irish guarantee was exceptionally broad. Not only did it cover all deposits, including corporate and even interbank deposits, as well as certain asset-backed bonds (―covered bonds‖) and senior debt it also included, as noted already, certain subordinated debt. The inclusion of existing long-term bonds and some subordinated debt (which, as part of the capital structure of a bank is intended to act as a buffer against losses) was not necessary in order to protect the immediate liquidity position. These investments were in effect locked-in. Their inclusion complicated eventual loss allocation and resolution options

With paragraph 8.50 going further on the issue of subordinated debt:

The inclusion of subordinated debt in the guarantee is not easy to defend against criticism. The arguments that were made in favour of this coverage seem weak: And it lacked precedents in other countries (although subordinated debt holders of some other banks since rescued abroad have in effect been made whole by the rescue method employed). Inclusion of this debt limited the range of loss-sharing resolution options in subsequent months, and likely increased the potential share of the total losses borne by the State.

Although it should be pointed of the €12.2 billion of dated subordinated debt covered by the guarantee only €1.4 billion matured during the period of the guarantee, none of which was in Anglo. The cost of including subordinated debt in the guarantee was, in the broad scheme of things, relatively small.

By September 2008, a banking crisis with massive costs was inevitable. The guarantee worked in one sense (kept the banking system open) and failed in another (limited ultimate loss allocation after equity to the State). Could the final fiscal have been lower under an alternative to the guarantee? Possibly. The issue is not so much the amounts (which are impossible to ascertain) but more that the guarantee decision cannot be discounted because “there was no alternative”.

There were alternatives and getting a better insight into why they were rejected is important both for understanding the past and preparing for the future (both here and elsewhere). Of course, it is probably more important to understand why the main banks started, and were allowed to continue, chasing Anglo from around 2002 which in the words of one AIB executive had “joined us for breakfast but now they’re eating our lunch”. There is some talk of a banking inquiry but we appear to be no nearer a concerted effort to find the answers to these questions.