The issue of Ireland’s corporation tax continues to generate lots of debate. Whether this is a good thing or a bad thing is also open to debate. At a recent Oireachtas Committee hearing a question on Ireland’s reputation was put to Prof. Frank Barry of Trinity:

Prof Frank Barry: That is a very interesting question. We speculated for some time about whether the US Senate hearings and reports would cause reputational damage for Ireland. The US newspaper, The Wall Street Journal, has had Ireland in its sights for a long time, complaining about Ireland’s tax regime. I spoke to one of its journalists from the US. It has a stringer in Ireland to whom I often talk, but I was called by a journalist in its US office and had a long chat on precisely this subject. They told me that the sense they were getting from Silicon Valley was that this was doing us no damage whatsoever. I talked with the IDA economists afterwards about this and they said that was exactly what they were hearing as well. That is interesting. I regard the The Wall Street Journal as a hostile source in that sense, so the fact it was saying that was interesting and certainly indicative. Yes, I think we might be over-paranoid here about the possible reputational consequences.

It is hard to know either way. Moving on. Yesterday’s Sunday Business Post had an article from David McWilliams on the topic. It included this assertion:

If these companies were to pay tax at the very low – by international standards – of 12.5 per cent, the exchequer would net Euro 12 billion in corporation tax per year. Euro 12 billion!

[Gated with the SBP but available here.] That is €8 billion more than the c.€4 billion that is currently collected and “these companies” are just the US-owned ones. The SBP piece is based on a recent article from the Finfacts.ie website.

US company profits per Irish employee at $970,000; Tax paid in Ireland at $25,000

Preliminary data [pdf] from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) on majority-owned foreign affiliates of US firms show that in 2010 (latest available), Irish-based firms reported net income of $95.6bn and a payroll count of 98,500 [pdf], which gives profits per employee of $970,000.

And here is where we run into problems. Depending on the exchange rate used that gives something around €75 billion of profits just from the US companies operating in Ireland. If we add in Irish companies and non-US foreign companies we can see that the overall amount of profit reported in Ireland could be expected to be well in excess of the above €75 billion figure. Is it?

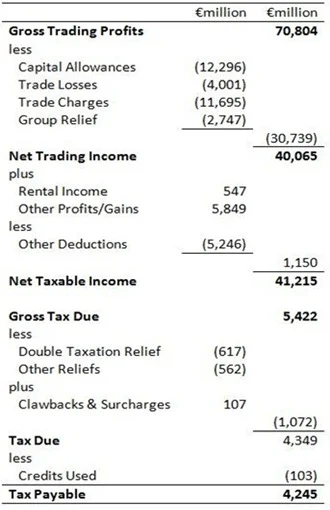

We can use the Annual Statistical Report from the Revenue Commissioners to find the amount of business profit that is declared in Ireland for tax purposes. In the 2010 report it was €70.8 billion. And here is a table from this post that shows how the €70.8 billion of gross profit is translated into the €4.2 billion of corporation tax that was paid.

The table also shows that the effective tax rate on the €41.2 billion of “Taxable Income” in 2010 was 10.3%. So what happened to all the profits that the US-owned “Irish-based firms” are making?

It is not the case that US-owned firms are massively under-reporting their profits from their Irish subsidiaries to the Revenue Commissioners; it is more the case that the profits from these companies are not resident in Ireland for tax purposes. The problem is down to the definition one uses for “Irish-based”.

For individuals, the US tax system recognises someone as being liable for US income taxes if they hold a US passport. That is, it doesn’t matter where they live or where they work, as long as they have a US passport they are liable for US income tax, with offsetting credits received for the tax they pay where they live. [For a discussion of this and recent changes brought in through the FATCA see this BBC article.]

For companies, US residency rules are also based on paperwork rather than activity. Under US law, the tax-residence of a company is the country where it is incorporated (i.e. what country’s ‘passport’ does it carry). All companies registered in Ireland are thus considered “Irish-based” under US law.

Ireland is similar in many respects but we have a slightly more intricate approach when it comes to determining corporate tax residency. Historically, the rule was (from revenue.ie):

All companies whose central management and control is exercised in Ireland (whether it is incorporated in Ireland or not) is regarded as resident in Ireland for tax purposes.

This was revised in the Finance Act, 1999, and now:

in general, companies incorporated in the State are resident in the State.

One of the exceptions to this is:

a company that is ultimately controlled by persons resident in the EU or in a country with which Ireland has concluded a double taxation treaty or is is related to a company the principal class of the shares of which is substantially and regularly traded on one, or more than one, recognized stock exchange in an EU Member State or in a tax treaty country.

Thus, some foreign-owned, Irish-incorporated companies will not be viewed as tax resident in Ireland if they are not centrally managed and controlled here. Prior to 1999 this was also possible for companies owned by Irish residents but the changes in the Finance Act 1999 tightened up the exceptions to the test of incorporation to foreign-owned companies only.

So what is at play here is that there are Irish-incorporated companies who, for want of a better word, “live” somewhere else. Just like our income tax system does not levy income tax on Irish nationals who live and earn money abroad, our corporation tax system does not levy corporation tax on (some) Irish corporations who carry out their activities abroad.

There is little that is unique or unusual about this. The issue is how our rules interact with rules of other jurisdictions, and the US in particular.

When the US Bureau of Economic Analysis says that US-owned, Irish-based companies had nearly $100 billion of profits in 2010 we actually have to go to Hamilton, Bermuda to find a good chunk of it (where Google Ireland Holdings is managed and controlled from) or Cupertino, California (where Apple Operations International is managed and controlled from).

Google Ireland Holdings is tax resident in Bermuda and pays corporation tax there on its massive global profits (the rate of CT in Bermuda is zero by the way). Apple Operations International is tax resident nowhere and thus pays corporation tax nowhere. Even though AOI carries out all its activity in the US, it is not resident in the US for tax purposes because it is incorporated in Ireland. Could Irish emigrants in the US avoid US income taxes because they have an Irish passport not a US one?!?

Both Google and Apple parent companies are liable for US corporation tax at 35% on their worldwide profits (with offsetting credits given for tax paid elsewhere). Because of the structure of their businesses and the nature of their profits (passive income generated by intellectual property) they do not have to pay this tax liability until the profits are repatriated to the US. In the case of Apple the profit is already in the US (and is managed in Reno, Nevada by Braeburn Capital) but because it is controlled by Irish-incorporated AOI it is still deemed “offshore”.

Google’s ability to shift profits to Bermuda where it has no activity or real presence is questionable and needs to be curbed; Apple’s ability to declare profits as tax resident nowhere is just wrong and needs to be stopped. Unilateral action by Ireland is unlikely to achieve either objective.

The OECD’s BEPS initiative may make some inroads in limiting the ability of companies to shift profits to no-tax, no-activity jurisdictions such as Bermuda. This might impact the scheme used by Google. The arrangement used by Apple is a bit more clear cut – companies should be tax resident somewhere. Sinn Fein’s Pearse Doherty has made proposals in this vein over the past few months – that Irish-incorporated companies can only be non-resident here for tax purposes as long as they are tax resident somewhere else, even if that is no-tax Bermuda.

We are probably not going to hear much at this level of detail in tomorrow’s budget but the Finance Act, 2014 may look to disassociate Ireland from the “ocean money” created by Apple. How might Apple respond? A likely response would be to move the management and control of AOI to Hamilton, Bermuda (which requires no more than a post-box) and do as Google does. Of course, the US could move to treat AOI as US-resident for tax purposes (it does engage in all of its activities there) as suggested by Sen. Carl Levin back in June but the reaction by the company would probably be the same.

There will be no €12 billion of extra corporate tax revenue for Ireland but hopefully madcap notions that there could be will become a little less frequent.

No comments:

Post a Comment