The impact of the €30.6 billion of Promissory Notes provided to Anglo and INBS, now merged as the IBRC, on the public finances is massive, but is often misstated. Over the weekend Stephen Donnelly wrote:

Over the course of 2010, the Fianna Fail Government invented a loan from the people of Ireland to Anglo and INBS. They essentially wrote a €31bn IOU, promising to pay it to the bank and building society over the following 20 years. In 2013, we are due to make our third payment on this, of €3.1bn.

But it gets worse. Now that we 'owe' them this €31bn, we must also pay them interest. This amounts to an additional €17bn over the 20 years. In 2013, the interest payment is €1.9bn. So contained in the 2013 forecasts is a payment of €5bn to Anglo and Irish Nationwide – two dead casinos, both under investigation on numerous fronts.

It is expected that Ireland will have a general government deficit of €12.6 billion, a €0.8 billion reduction on 2012. In an earlier paragraph it is claimed that the 2013 deficit should actually be €15.7 billion.

It is true that the headline figure looked at by the troika will fall by about €800m. But due to some accounting wizardry, a full €3.1bn of the €5bn to be paid to IBRC isn't included. When you add that in, the deficit will in fact grow, by a whopping €2.3bn.

As discussed below this is a mis-interpretation of the impact of the Promissory Notes on the deficit.

The recapitalisation of Anglo/INBS in 2010 could only be achieved with the transfer of an asset to the banks to support their balance sheet. The government didn’t have €30 billion of cash lying around, had little potential to borrow it, so an asset was created for the banks.

The Promissory Notes are recorded as a loan asset on their balance sheets. The repayment of the Promissory Notes is the repayment of this loan from Anglo/INBS to the state. However, unlike typical loans the in this instance the borrower (the state) is repaying a loan without receiving any of the money in the first place.

By viewing the Notes as a loan from Anglo/INBS to the state it is easier to see that the repayment of the Notes do not increase public debt. If the repayments are made from current resources the level of debt will fall; if the repayment is made with borrowed money the level of debt is unchanged. The latter is definitely the case.

For 2012, Ireland will have a general government deficit of around €13.4 billion. The impact of the Promissory Notes on this is nil. The annual €3.1 billion payment was made at the end of March (a government bond was issued to BOI to get the cash from them). This simply swapped one form a debt (the loan liability to IBRC) for another form of debt (the bond liability to BOI).

The capital amount of the Promissory Notes was recorded in full in the 2010 general government deficit when Ireland ‘borrowed’ the money from Anglo/INBS.

As the Promissory Notes are a loan the value of the asset on the balance sheet must reflect the value of the loan. A €31 billion loan to be repaid over 20 years would not be worth €31 billion if there was no interest on the loan. The book value of a €31 billion zero-interest loan would not have been sufficient to recapitalise these bust banks. They needed an asset worth €31 billion so an appropriate interest rate had to be applied to the loan.

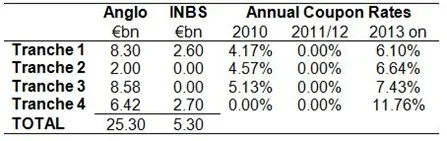

As the money was being ‘lent’ to the government over a long period the interest rate chosen was the equivalent-term government bond yield from the secondary market on the day the Promissory Notes were issued. Here are the rates on the four tranches.

As can be seen the interest charged on the loan in 2011 and 2012 was zero. There was an ‘interest holiday’ built into the loan for those years for some reason (probably to improve the aesthetics of the annual deficits). There is a higher coupon from 2013 on to make up the shortfall generated by this interest holiday.

Interest will resume being charged on the loan from the first of January. In 2013 the interest bill on the Promissory Notes will be around €1.9 billion. However, it is important to note that this is accrued interest and is added to the capital amount of the loan rather than being paid.

The annual €3.1 billion payment does not change because of the end of interest holiday. This is still made and the current structure is that this will be paid each year up to 2023. What changes is the reduction in the capital amount effected by the payment as some of this is consumed by the interest. This is shown in the following table.

The “Interest Due” is the amount of accrued interest charged on the loan over the 12 months to the end of March each year. The interest charged against the 2011 payment relates to the amount issued during 2010 prior to the start of the interest holiday. The interest charged against the 2013 payment will reflect the interest accrued from the first of January to the end of March next year.

Whereas the 2012 payment reduced the Promissory Note debt by virtually the entire €3.1 billion payment, the 2013 payment will reduce the debt by €2.6 billion. The March 2014 payment will be preceded by a full year of accrued interest and will reduce the debt by €1.2 billion.

This distinction between capital and interest doesn’t matter. Each year the IBRC will get €3.1 billion from the government. Just like all loan repayments the money doesn’t come under different headings. It is just a loan repayment.

Also, as the IBRC is 100% state-owned the transfer to the IBRC doesn’t make a difference to the overall position of the state. What really matter is when the IBRC uses the money to meet its own liabilities. The structure of the Promissory Notes makes absolutely no difference to value of these and these are the ultimate liabilities that have to be covered. The Promissory Notes are just a conduit to provide the money to cover these.

The main liability of the IBRC is now the Exceptional Liquidity Assistance (ELA) it has drawn down from the Central Bank of Ireland which it obtains at an interest rate of around 2.5%. Prof. Karl Whelan has shown that the IBRC will be able to repay its ELA liabilities using its own assets (proceeds/repayments from remaining customer loans) and the annual payments on the Promissory Notes by 2022. There will be no need for the subsequent payments.

Based on current interest rates the IBRC needs €31 billion at around 2% to repay its ELA obligations. The fact that it received €31 billion at around 6% means that the IBRC will be able to repay the ELA faster than the government has to repay the capital on the Promissory Notes. Once the ELA is paid off the remaining Promissory Notes can be cancelled.

When the IBRC repays the ELA it has drawn down from the Central Bank the money repaid goes out of existence and is “burned”. Most of the interest paid by the IBRC to the Central Bank is a profit for the Central Bank (they just created the money) and this is circulated back to the government via the payment of Central Bank Surplus to the Exchequer Account.

There will be around €0.5 billion of interest added to the Promissory Notes by the time the €3.1 billion annual payment is made next March. For the full year to December the amount of interest accruing on the Promissory Notes will be around €1.9 billion and this will be added to the General Government Deficit.

This is summarised in this table from the last page of the recent Medium Term Fiscal Statement. Click to enlarge.

As explained above the interest costs after 2022 are unlikely to happen. The problem is the interest cost now. The €1.9 billion interest cost for 2013 is added to the deficit but we are not really paying it. We are paying for the cost of the Anglo/INBS disasters and whether the money given them is labelled interest or capital does not change the size of the hole to be filled.

Some of the interest will circulate back to the government via the IBRC and the Central Bank. Another portion will be used to repay the IBRC’s ELA liabilities which means the Promissory Notes can be cancelled some time around 2022. Very little of the interest is lost.

The net external interest cost of the Promissory Notes/ELA construction is the ECB’s main refinancing rate (currently 0.75%) which the Central Bank pays to the Eurosystem as a payment for creating the money used for the ELA.

The figure to focus on is the final cost of the Anglo and INBS disasters. This is going to be more than €30 billion and is an unbelievable waste of money. It is money that went to depositors.

As Patrick Honohan said recently:

“It would have been better had Anglo and INBS been put into resolution as soon as it became clear that their capital was going to be wiped-out by unavoidable losses on developer loans. This should have been evident before September 2008, but was not, leading the Government of the day to include these two failed entities in its blanket guarantee.”

Repaying those deposits is costing us dearly. A change to the Promissory Note arrangement by March is possible but getting one that results in substantial savings is improbable.

Hi Seamus,

ReplyDeleteThe 0.75% that the Central Bank of Ireland pays to the ECB on the ELA that was created for IBRC, is also recirculated isn't it, after deducting the ECB's operating costs.

And separately, isn't one proposal presently not to pay the promissory notes at all, that is for the State to renege on its commitment, and in that case, just as when the promissory notes were created resulted in an increase of GGD, wouldn't such a reneging in the first instance result in a decrease in the GGD.

Of course in the second place, if there was a reneging, then IBRC would not be able to repay ELA to the Central Bank, but then would that loss at the Central Bank circulate to the Government via a deficit on the Central Bank operations (this year Central Bank returned €1bn to Govt, could that become a €27bn deficit in one year if IBRC defaulted on ELA).

@ namawinelake,

DeleteI'm not sure the interest paid by the CBoI is fully refunded. I could be wrong but I think the profit made by the ECB is refunded to the eurozone National Central Banks in proportion to their contribution to the capital key of the ECB. The CBoI's contribution is around 1.6% of the contribution from eurozone member's.

It is hard to say what will happen with the Promissory Notes. It is possible that nothing will. I would think that a cancelling of them and the subsequent non-payment by the IBRC of its ELA liabilities has a very low probability.

I think I understand the circular reference to the money flows but there is one point that is unclear. If the net cost is marginal then why is €1.8bn of loan interest added to the general government deficit? Surely, there should be an offset for the income generated?

ReplyDeleteHi Anonymous,

DeleteThere is. It is the surplus income from the Central Bank. This was €958 million this year and the White Paper projects it to be €1,040 million next year. That is where some of the interest flows back in. The remainder of the interest is used by the IBRC to repay its ELA obligations.

The problem, such that it is, is that in 2011 and 2012 no interest from the Promissory Notes was added to the general government deficit. There was an interest holiday built in for some reason.

So in 2012 there was a €1 billion receipt from the Central Bank but no corresponding expenditure. Next year the interest expenditure will be included. The interest is also higher because of the interest holiday.

We are going from a situation this year where the deficit is made to appear better because only the revenue (central bank surplus) is included to one next year where the deficit is made to appear worse because the expenditure (promissory notes interest) is included.

The interest payment is in the general government accounts because the IBRC is classed as a state-owned financial institution rather than as a part of the general government sector. So it is a flow from the government sector to the financial sector. The flow makes the deficit look worse now, but the overall debt position will be improved when the promissory notes remaining are cancelled after the IBRC has repaid its ELA liabilities. It's the case that we're in a mess right now, and saying things will look better in a decade's time does nothing for us.

Seamus

DeleteThanks for claryifying that. It would appear that there are potential solutions;

1. Follow the example of major corporations when interest rates fall and "re-finance" the debt. The interest bill is high because of the various rates from 6% to 11% were used. Refinance and reduce this to circa 4%.

- I recognise that there is a circular funds flow but because the interest expense is recognised in the GGD but not the income, we need to lower the interest expense.

- If the interest expense is reduced, the impact on GGD is reduced and therefore we reach the magic 3% target quicker.

2. The alternative would be to classify IBRC as part of the general government sector but that may have a detrimental impact elsewhere on the nation's balance sheet.

Today Stephen Donnelly has a budget proposal which includes not paying any more to the promissory notes.

ReplyDeleteWould you mind explaining if you see that as a good or bad thing?

In the context of "Repaying those deposits is costing us dearly. A change to the Promissory Note arrangement by March is possible", what is the _best_ thing that could happen, from your perspective?

Hi edanto,

DeleteIf we could avoid paying the promissory notes it would be a good thing. However, doing so would do little to the deficit. The capital repayment on the Notes is not counted as part of the deficit. It would be great not to have to repay them but the deficit would remain largely as it is. As a proposal to reduce the deficit it is largely ineffective but it would reduce our debt.

The best thing that can happen is that the Promissory Notes are cancelled and the IBRC's ELA liabilities to the Central Bank are annulled. There is close to zero chance of that happening in the absence of a collapse of the euro.

The best thing that can happen is that the repayment of the ELA (and as a result also the Promissory Notes) is delayed for a very long time - decades. This is again unlikely but it would be a big help.

The Promissory Notes/ELA funding is incredibly cheap and holding on to it for as long as possible would be a beneficial. Repaying the Promissory Notes and then the ELA means that very cheap debt (0.75%) is being replaced by much more expensive debt (c.4.0%). Again this is unlikely to happen.

A sideways view on this, appropriate on budget day, is to see if there can be a net gain to the government on its equity shareholding in the Irish operational banks, i.e. banks other than IBRC, and - by means of a 'special' share - to voluntarily cancel the promissory note and replace it with the 'special' share. As the end-date for the promissory note is already set at 2031, that leaves 19 years for the government's 60% equity ownership (approximately) to reach a period of sustainable profits, crucial to its market value, which when taken into account with the balance sheet net worth of its equity will likely yield well above the full promissory note obligation. For the current IBRC balance sheet this could all be set up with a bond financial instrument. The ECB's input would be to discount the cost to the Central Bank of Ireland to a guaranteed 'negligible' amount, and to agree the resetting of the promissory note. The IBRC would be required to transfer all its loans to NAMA, paid via eurobor borrowing - which in turn was passed over to the Central Bank of Ireland re ELA, part of, - and to end all banking activity and clean out its balance sheet so that all that remained was ELA/reset Promissory Note. The NPV wouldn't matter at that stage.

ReplyDeleteAs for the potential for the Irish operational banks: The current balance sheet equity value (30 June), when the government's capital loans/preference shares are shown as liabilities, is around €20 billion, giving the government's share (60%) as €12 billion. From its deleveraged loan book of around €195 billion, the bank' loan book will at least inflation upwards by 2031 to over €300 billion. I suggest an after-tax profit of 1.5%, i.e. €4.5 billion, which when shown to be sustainable, will contribute handsomely to its market value.

I estimate market value to be 5-times sustainable profit plus balance sheet net worth. This explains why a period of ownership during which there is a steady annual sustainable profit is vital for a good market value.

The equity costs have been €13.6 billion, not €30 billion. The capital loans, €8.3, can be repaid at par from general current assets/liabilities, the €1.3 billion invested in Irish Life will see itself right, I'm sure, while the €6.054 billion 'Special Capital Consideration' paid to AIB will have to be offset against banking crisis income generated, i.e. Central Bank profits + Bank guarantee fees.

Such an action would be equivalent to giving a €64.1 billion stimulus boost to the economy (cost of bailout to date) and giving immediate hope.

Hi Seamus,

ReplyDeleteI’ve read through your analysis, and while I have no problem with your description of the Pro Notes, we differ on some of the conclusions.

As you point out, the 2013 GGB includes an interest payment of €1.9bn. It doesn’t matter if this is not a cash payment (I’m assuming that’s why it’s not included in the 2013 exchequer balance). The ‘no change’ 2013 Estimates show a GGB of negative €15.1bn. With 7.5% of GDP forecast to come in at €12.6bn, this creates a gap of €2.5bn which has be closed through budgetary measures. So without the interest payment of €1.9bn being recorded, the gap would be just €0.6bn – that’s one hell of a difference, and opens up far more options for a combination of fiscal consolidation and targeted investment.

I would also suggest that the capital payment matters a great deal. Yes, it gets taken out in the walk between the exchequer and general Government balances, but it still gets paid. The only reason it gets taken out is because the overall Government position doesn’t change, as we write down the total amount ‘owed’ to IBRC. So putting aside the accounting treatment of it (which I accept is legitimate, and necessary to comply with the relevant EU guidelines), the reality is that we pay over a large chunk of cash to IBRC, and claim that it doesn’t affect our net position, because we’ve just written down our loan to them by the same amount. That really only stands up if we got €31bn worth of assets for our ‘loan’, which, we can probably all agree on, we didn’t. Either way, we’re still paying the cash. It doesn’t matter that it doesn’t lower the GGB – once the €2.5bn reduction is met in other ways (or the €0.6bn if you don’t allow the interest adjustment), then the capital payment can be redirected to a productive use, if you decide to write down the ‘loan’.

The claim that we’ll get the interest back is also questionable. I’ve tabled various questions to Noonan on this, asking for confirmation that the interest will be returned. His replies have been reported, and the thrust is that he cannot give an estimate, but believes that “the bank remains of the view that there will be a small return to the State at full resolution.” The extent of the circularity of the payments is unclear, but what is clear is that, regardless of what percentage we may ultimately recoup, we are paying out right now, just when we need the money for further consolidation and investment.

No doubt you may disagree with some of this ;-)

Stephen.

It's hard to argue with the conclusion that not having to incur €1.9 billion of extra cuts would be a great thing for the country, but from a practical point of view, what can the government do about it?

ReplyDeleteAs Seamus suggested, I think a unilateral default by Ireland is highly unlikely. Would Minister Noonan even threaten that during negotiations? I doubt it.

Perhaps the ECB will agree to an extension or deferral of the repayment period, but the likelihood is that the net present value of the repayments will need to remain constant. So realistically, I think the best we can hope for is a 'kick the can down the road' solution, which actually might be no bad thing if it gives the economy a chance to return to growth in the interim.