Nominal House Prices

Back in October, the CSO produced a publication to mark 50 years of Ireland and the EU. Included in this was a series of annual average house prices from 1970 to 2019. The values in the table are charted below and they show the average annual house price rising from €6,700 in 1970 (when converted to euro) to €295,700 in 2019.

The chart takes all the values as published by the CSO with the additional values for 2020 to 2022 taken from the CSO’s databank. The series closely follows other nominal house price series for Ireland (such as Fred’s) except for 2010 to 2015, with the chart above understating the post-2008 fall in house prices (which continued to 2012) shown by other indices – including the CSO’s own Residential Property Price Index.

The average for 2023 is likely to be around €370,000 and this estimated value is also shown above. Here are the CSO’s notes on the original table:

Note that 1970 – 2009 data is based on mortgage data whereas the 2010 – 2019 CSO data is based on Stamp Duty returns from Revenue. Figures for 1970 to 1977 are new prices only while all others are for new and second-hand properties in Euro or Euro equivalent.

The methodological change in 2010 and the low level of transactions, impacting the composition, likely explain the larger nominal fall of around 60 per cent) shown elsewhere. We will proceed with the values as given in the table. Our primary interest is a comparison of current prices to what they were in the 1970s, 80s and 90s rather than to what they were in the depths of the post-2008 recession.

In nominal terms, house prices are far higher than they were in the 1970s, 80s and 90s. In simple nominal terms, at €370,000 houses prices now are almost ten times higher than the average price from 1970 to 1995 (€38,700).

Indeed, the latest estimates are a record high for the series exceeding the previous peak of €350,000 from 2007. The chart also shows that in the last 50 years, Ireland has had just one period of nominal house price declines: 2008 to 2012.

But these numbers are of their time. Just how does €6,700 from 1970 compare to €370,000 in 2023? The price of everything has changed in the interim. Just how can we tell which year had more expensive housing?

Inflation-Adjusted House Prices

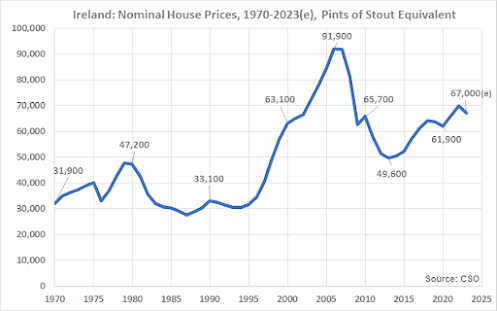

We can try to put the prices in terms of other products. The CSO collect national average prices for a range of items. Since 1983, they have been publishing a national average prices for 567ml of draught stout in a licensed premises. Using this, and some additional sources to extend the series back to 1970, we can put the average house price in any given year in terms of the number of pints that could be bought that year for the same sum.

In 1970, the average price of a pint was 21c and with an average house price of €6,700 the equivalent price of a house was 31,900 pints. For 2023, the average price of a pint is put at €5.48 and our estimated average house price of €370,000 puts 2023 house prices as equivalent to 67,500 pints of stout. Pint glasses mightn’t make good lenses but using them points to average house prices being about twice as high than they were 25 to 50 years years ago and not the ten times higher as the unadjusted nominal house prices suggest.

Using pints, we can see that houses were at their most expensive in 2006/7 – equivalent to over 90,000 pints. And the pints equivalent for 2023 is pretty much where it was back in 2002. Nominal house prices are well up on where they were in 2002 (€213,000 versus €370,000) but so too is the price of a pint (€3.21 versus €5.48). The current level is about twice as high as the 34,700 it averaged from 1970 to 1995.

Now maybe recent house prices are flattered by putting them in pints equivalent – due maybe to the impact of Excise increases. The CSO’s 50 years in the EU publication also gives us some other prices to use.

For example, a white sliced pan was 15c in 1973 and is €1.66 now. Taking the same approach as above shows that average house prices have gone from the equivalent of 60,100 sliced pans in 1973 to an estimated 222,400 now.

Perhaps for reasons for interest, it is harder to track down the full series for the national average price of a sliced pan. The pattern is as before and again we see that the peak level was seen back in 2006 – when the average house price was equivalent to over 300,000 sliced pans.

Real House Prices

While messing about with pints and sliced pans is useful for showing that nominal prices now are not the same thing are nominal prices from the past, it is whimsical at best. A much better approach would be to take a much broader set of prices such as the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Figures from the CSO, show that prices as measured by the CPI in 2023 are around 1,420 per cent higher than they were in 1970. This means that spending €6,700 in 1970 (the nominal average house price) would be equivalent to spending 6,700 x 15.2 =101,900 if faced with the 2023 prices in the CPI.

We can use this to convert the nominal house price series into real prices using a constant price deflator. We can choose any year as the base. We will use 2023, thus the 2023 nominal and real figures are the same. The real figures for all other years are found by determining what the nominal house price for that year would be equivalent to if faced with the 2023 prices in the CPI.

The general pattern is roughly in line with what we got using pints and sliced pans. As expected using pints flatters current house prices: the price of a pint is around 26 times higher than it was in 1970 compared to a 15 times increase for the CPI. Sliced pans did the opposite as their price is around 11 times higher.

Anyway, using the CPI-deflated house prices we can see that Ireland had two sustained periods of real house price declines: the first from 1978 through to 1986 and the second from 2007 to 2012. Again 2006/07 shows as the peak.

Thinking in constant price terms isn’t always that intuitive and the numbers can be a bit messy. A better way to present real house prices is as an index: select a base year – typically set to 100 – and get values for all other years relative to that.

The shape of the charts are exactly the same. There was an extraordinary run-up in real houses from 1996 to 2006 when they more than trebled. When CPI adjusted, house prices in Ireland now are just over three times higher than what they averaged from 1970 to 1995. Why is this?

There are lots of reasons. One reason is that buying a capital good such as housing is not the same as buying consumption goods. Income may play a different role in the demand for housing compared to the demand for individual goods for consumption.

House Price to Income Ratios

To see whether house prices have become more expensive we can check how they have changed relative to income. Again, we can turn to some long-term series provided by the CSO. One such is the historical series published for the Average Industrial Wage (AIW) which goes all the way back to 1938.

We just need it from 1970 and this shows that the AIW now (€856 per week) is 22 times higher than what it was in 1970 (€23.20 per week). One simple thing we can do is divide the average nominal house price for each year by the annual Average Industrial Wage for that year. This gives:

In 1970, average house prices were around 5.5 times the annual average industrial wage. By the depths of the recession of the 1980s this has fallen to 3.6 in 1987. It remained around four up to 1994 and then exploded, with average house prices reaching almost 11 times the annual industrial wage in 2006 and 2007. It has remained on a rollercoaster and recent figures put average house prices at over eight times the AIW.

- 1970: €23.28 x 52 = €1,210 ; €6,700 / €1,210 = 5.5

- 1990: €286 x 52 = €14,866 ; €63,900 / €14,866 = 4.3

- 2006: €601 x 52 = €31,262 ; €339,500 / €31,262 = 10.9

- 2023: €856 x 52 = €44,512 ; €370,000 / €44,512 = 8.3

Relative to consumer prices, we saw that house prices in 2023 were around three times higher than what they averaged from 1970 to 1995. Relative to the average industrial wage, we see that house prices are around two times higher than what they averaged over the same period.

Before moving away from income we note two things:

- The share of workers earning the AIW has declined

- Housing is bought by households, not earners.

The AIW is useful because we have a long-run series for it. However, the weekly earnings of “production, transport, craft and other manual workers” in industry sectors (NACE B to E) may not be as representative of earnings as they previously were. Workers in many services sectors will earn less than the AIW. The share of workers earning more may have also have increased.

We also note that recent decades have seen a significant shift to more dual-income households. Thus a measure of household income may be more appropriate than the individual-level earnings data.

To get household income we turn to the national accounts. Definitions matter but here we will just note that we are using Gross Household Disposable Income. In national accounts, ‘gross’ means it is before depreciation and ‘disposable’ means after taxes and transfers. Data from 1995 on is available from the CSO and we will use the nominal growth rates in Stuart (2017) to extend the series back to 1970. We also need the number of households and these are taken from the Census and interpolated for the intra-Census years. This gives us figures for disposable income per household.

For 2022, CSO data puts gross household disposable income at €138.2 billion. With the Census reporting 1,841,152 households for the same year that gives us a figure of just over €75,000 for disposable income per household. With an average house price of €357,000 in 2022, the ratio of house prices to household disposable income is €357,000 / €75,050 = 4.76.

We can do this for all years since 1970 to get the following:

Again, we see the peak was reached in 2006, when average house prices were almost six times average household disposable income. It is likely to come in around 4.6 times for 2023, which is around where it was in 2002.

For our long-term comparison, this ratio of price to income averaged 2.6 from 1970 to 1995. The means the ratio is now 1.75 times than what it was over that period. The increase is lower than what was shown using individual earnings but not hugely so.

Mortgages: Rates, Repayments and Deposits

Before concluding that housing is far more expensive than it was 25 years ago we must look at how most households pay for housing: mortgages. This introduces interest rates which are hugely important for determining mortgage payments. Consider two 25-year mortgages for €100,000 which only differ by the interest rate charged. Let the first have a rate of 4 per cent and the second a rate of 12 per cent. What will be monthly repayments be?

- €100,000 25-year mortgage at 4% interest = €527.84

- €100,000 25-year mortgage at 12% interest = €1,053.22

The difference in the interest rate leads to a monthly mortgage payment that is almost twice as high. Interest rates matter! And in Ireland mortgage interest rates have varied a lot.

The CSO have long-term data on average mortgage interest rates – see Table 10 of this 2003 publication marking 30 years of Ireland’s EU membership. Data for recent years are taken from the interest rate statistics of the Central Bank of Ireland. They give the following series of annual averages:

From 1970 to 1995, mortgage interest rates averaged 11.4 per cent. They are now around 3.6 per cent (though rising).

We can get indicative monthly mortgage payments with three parameters:

- The initial amount borrowed

- The length of the mortgage

- The interest rate charged

To make a comparison we will assume that the initial amount borrowed is 90 per cent of the average house price in each year. We will use a term of 25 years in all cases and apply the interest rate for each year as shown above. With these, we can get an indicative monthly mortgage payment and we will put that as a share of monthly average household disposable income. And this shows:

From 1970 to 1995, the indicative monthly mortgage payments averaged 29 per cent of household disposable income. This is higher than the current estimate which is around 25 per cent of household disposable income.

The above shows that the peak for mortgage payments to income was 41 per cent back in 1982, exceeding the local maximum of 37 per cent from 2007. As we have seen 2007 corresponds to the peak of real house prices. 1982 corresponds to the peak of mortgage interest rates which averaged 16 per cent over the year (which is also shown in this blog post from the Governor of the Central Bank).

It should be pointed out that this is very much a point-in-time assessment of mortgage payments to income. Of the three parameters used, only one remains unchanged: the initial amount borrowed. Key for determining the payment-to-income-ratio are the interest rate charged and the household’s disposable income. Both of these will change over time for borrowers. Interest rates trended down through the 80s and 90s while household income has trended up. For individual borrowers this will reduce the ratio of the monthly mortgage payment to household income.

The point-in-time assessment is useful, though, for the initial payment burdens faced by prospective purchasers. And as we have seen, this burden is now slightly lower than what it averaged over the period 1970 to 1995.

And this is before increased life expectancy and longer duration mortgages are taken into account. The above analysis assumed a 25-year term for all mortgages. In the last 20 years, mortgages with terms of 35 years have become prevalent.

Although the age of first-time buyers has increased this has been somewhat offset by increased life expectancy. In the early 1970s, an Irish male aged 25 had a life expectancy of a further 46 years (i.e. to 71). The detailed results based on Census 2016 give an Irish male aged 25 a life expectancy of a further 55 years (i.e. to 80). It is likely to be now another year or two higher again.

It is not all a one-way street from lower interest rates though. Present-day borrowers may benefit from lower interest rates but higher prices means they are required to have a bigger deposit.

From 1970 to 1995, a ten percent deposit based on the average house price was 26 per cent of average annual household disposable income. In 2023, a ten percent deposit is equivalent to 46 percent of average annual household disposable income. Prospective buyers may also need even higher deposits due to the Central Bank’s macro-prudential rules on mortgage lending. And that is what the evidence would appear to bear out.

The overview of new lending from the 2019 Household Credit Market Report shows that the deposits of FTBs in Dublin were just under 90 per cent of household income and they were 72 percent for Non-Dublin FTBs. Higher deposits means it is harder to access those lower interest rates. And we haven’t even mentioned ever-increasing private rents which further add to the difficulty of gathering that deposit.

Summary

Here is a summary of the indicators presented:

By most metrics housing is more expensive than it was 25 to 50 years ago. Nominal prices are almost ten times higher compared to what they averaged from 1970 to 1995. When adjusted for the general increase in the price level, real house prices are around three times higher now than the 1970-1995 average. Using income we see that house prices are under two times higher than that average.

When looking at mortgages we see that the measures are lower. Mortgage rates now are around one-third of their level from 1970 and 1995 and though, house prices have increased, an indicative monthly mortgage repayment is now a lower share of average household income. Moving in the other direction is the deposit required which is now almost twice as large as a share of average household income compared to what it was in the 70s, 80s and early 90s.

Compared to 2003, most of the indicators are actually little different. Inflation-adjusted house prices and price-to-income ratios did rise, fall and rise again over the period but are back close to 2003 levels. Mortgage interest rates and the payment-to-income ratio are also close to 2003 levels.

The ratio of a 10 per cent deposit to income is also similar but the lending environment is much different. Back in 2003, borrowers were more likely to be lent more than 90 per cent of the purchase price and factors like parental guarantees were much more widespread. The Central Bank’s macro-prudential lending rules now restrict these with a greater requirement for borrowers to have the deposit to hand.