One of the sessions at the World Economic Forum in Davos last week was on corporate tax avoidance. A recording of the session is here while two contributions from one of the panelists, Davide Serra are reproduced below [timestamps].

[16:15] In my view what we have here is very simple. I think we're lying to voters and I think business has to stand up and do numbers. So, for example, and I just go through a couple of simple numbers.

Google, not to refer Apple, in Ireland, and I use Ireland simply because the Finance Minister, we can do this the same for Luxembourg and The Netherlands, booked revenue of 22.6 billion euro, 22.6 billion euro in 2015. They paid to Ireland only 48 million euro.

Ireland says has a tax rate of twelve and a half per cent which is competitive. There is only one problem, in Ireland if you set up a business and the business is 100 per cent controlled abroad you basically pay zero taxes. So, it's correct within tax law in Ireland. They are correct. There is only one problem what happens if everybody were to book their foreign subsidiary in Ireland. And that's what happens.

So, running the numbers, this is realised 60 billion euro of tax elusion - evasion. I consider borderline to criminal in three Member States. Of course, they're not going to say, and they're not going to put themselves on the back list. It's easy to put Samoa Islands or someone else.

And why is the system 100 per cent rigged? Because too many benefit out of it: the consultants; the auditors; all the bureaucrats.

And, so I think it is very simple. You need to have by law that any corporation that is listed and wants to have global standards give me one number: total tax paid, where, total number.

If you have asked this to Facebook, take Facebook, they pretend to be good citizen. Now they paid four thousand pounds, four thousand pounds of taxes in 2014 in the UK. If I take reported, if I add every annual report of Facebook globally and I see what's the tax paid, I see the number, it's zero. They post ten billion dollar profit.

So, explain to someone if I add every annual report that you file in every country and you pay zero taxes. And you pay zero taxes it is very simple. If you are listed company in the world you must give me one number, total tax paid in which country. And all this discussion, ends.

[28:00] So it's very simple. Within Irish tax code, if you have a multinational that is 100 per cent directed outside Ireland, de facto, you are not taxed. Hence, and this is the law, and I am happy to challenge you in the rule of law.

So, Google 22.6 billion euro revenue in Europe in 2015. How much taxes were paid in Ireland? Forty eight. Equates to zero point zero zero two. Better deal than Apple. Hence, every study ends the same and I run my regulated business by the CBI in Ireland. So, I am a businessman in Ireland.

Ireland, if you are in Ireland, you are charged twelve and half per cent. If you are someone global, you put everything there, they don't see you. Now this has equated to more than twenty billion euro elusion per year of European taxes.

When as a European citizen I look at an Irish citizen: since you joined the European Union, Ireland had net contributed to the EU budget 150 million euro. Why are you allowing elusion, so less revenue, losses to European citizens of 20 billion, it’s a ratio that is five hundred times per year.

I say, and I love Ireland and I have a business in Ireland and it's a great business community, tax everyone no matter where they come from at twelve and a half per cent because if you tax people at zero point zero zero two this is a joke.

[56:00] For me it’s very simple: every corporation in the G20 to report how much tax they paid in local currency, country by country.

Let me give you a simple example. I know Google in Ireland 22.6 billion of revenue; only five thousand employees. So each employee in Ireland, in Google, generates 45 million revenues.

And, hence, there is only one way, tell me how much taxes you paid in each country, every corporation. And every citizen through their pension fund, mutual fund, ETF if you don’t see the number I’m sorry I blacklist the institution.

Because before we wait for politicians to agree BEPS, SEPS, OECD and all this acronym there has been ten year of 600 billion euro tax elusion, 6 trillion euro. As a result it’s time to act; no more words. And it’s up to citizens to stand up.

At the end, Professor Joseph Stiglitz said “it is only outrage that will stop and reform the system”. The contributions from Serra satisfy the outrage requirement and would do well if the gauge by which they are judged is that “it wasn’t what you said, it wasn’t how you said it, it was how you made me feel”.

But what is said matters. And the simple issue with Serra’s contribution is that it is wrong. The system of collecting taxes from the profits of companies has numerous problems but if the proposals for reform come from outrage rather than analysis we could end up with something that is worse than what we have now. Let’s look at some of the claims.

First, a 0.002% tax rate for Google. As a businessman he is surely aware that a corporate profits tax is charged on corporate profits not revenue. Here is Google Ireland’s income statement for the past two years.

Serra focused on 2015 and we can see that, yes, Google Ireland Ltd. had revenue of €22.6 billion in 2015. The first thing to note is that €47.8 million is 0.2 per cent of €22.6 billion not 0.002 per cent. His sums were out by a factor of a hundred. Ah, but we need outrage on this so that’s ok.

But comparing tax to revenue is not ok. We have to get to profit before we have something we can compare to the tax bill. So what expenses does Google Ireland Ltd incur?

The first is €5.5 billion in 2015 for “cost of sales”. Per the accounts “costs of sales” is:

So, this is the money paid to third-party sites to host Google ads. After we subtract this €5.5 billion we get to gross profit, then we need to subtract administrative expenses to get operating profit. The administrative expenses are made up of three items.

Unfortunately, we don’t get a direct breakdown of these in the accounts but we can get a fairly good handle on them as we did here. In 2015, staff costs for Google Ireland Ltd. were €365 million with other ongoing costs likely coming to a couple of hundred million euro as well.

Google Ireland pays about €4 billion to other Google companies in its market area (EMEA) for sales and marketing services carried out by the staff there (with each of those companies also paying some corporate income tax in the countries in which they operate). Google’s 10k form shows that it incurred a current tax charge of $723 million outside the US in 2015 and this rose to $966 million in 2016.

But back to Google Ireland Ltd. We still have around €12 billion of the administrative expenses shown in the 2015 accounts to the explained. We can see what this is from this note from the accounts of Google Netherlands Holding B.V.

In 2015, Google Ireland Ltd. paid €12.0 billion in royalties to Google Netherlands Holding B.V. who in turn (along with some royalties received from Google Asia Pacific Pte Limited) paid that on in a royalty expense to Google Ireland Holdings which is based in Bermuda.

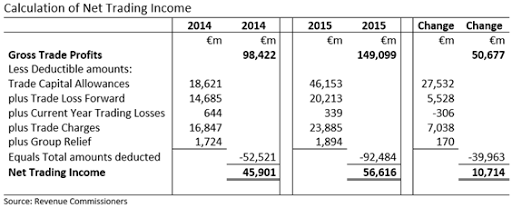

But back to Ireland. After some interest income, and expense, we get the profit on ordinary activities of Google Ireland Ltd. This was €341.2 million in 2015 and on this the company had a tax charge of €47.8 million giving an effective rate of 14.0 per cent. The accounts explain why this differs from Ireland’s headline 12.5 per cent rate:

We can see that among the adjustments the company has some expenses which were not deductible for tax purposes (possibly entertainment expenses), had some income that was taxed at higher rates (Ireland has a 25 per cent Corporation Tax rate on non-trading income such as interest), has some income that was not subject to Corporation Tax at all, and also incurred some withholding taxes in other jurisdictions. Sum through those and you get the €47.8 million tax charge for the year.

Does putting this number over revenue and spouting about 0.002% tax rates mean anything? Not one thing. And wouldn’t even if the arithmetic was correct. If there are issues to be raised it has to be with the expenses deducted to get from turnover to operating profit.

Can there be a problem with the €5.5 billion Google paid to other parties that allowed them to host ads on their sites? Surely not. Or the €5 billion of staff and other expenses that Google incurred in Ireland and across its market area. Again, surely not.

Maybe there are issues with the €12 billion license royalties paid by Google Ireland? Maybe. But Google Ireland is selling ads on a platform that was developed somewhere else. That the Irish company has to pay a royalty for the right to use that platform is not that surprising.

Of course, the technology is developed in the US and it would seem natural that the royalties would flow there, but Google has availed of provisions in the US tax code that allow it to move “offshore” the license to use its technology outside the US and this license is held by a company based in Bermuda.

When the structure was originally set up Ireland would have charged a withholding tax on the outbound royalty payment if it was made to to Bermuda so the money doesn’t flow directly to Bermuda but instead makes a brief stop in The Netherlands. Ireland is not permitted to charge withholding tax on such payments made to The Netherlands because of the EU’s royalties directive disallowing them for such flows between EU Member States. The Netherlands then allows the money to flow to Bermuda without being exposed to a withholding tax there.

So, does the €12 billion stay untaxed in Bermuda? Some of it, yes, but not all of it. To get the international license for Google’s technology, the Bermudan company must make a cost-sharing contribution to the overall research and development costs incurred by Google Inc. This contribution is based on the size of the market the license covers.

It is likely that the Bermudan company has a license that covers markets that generate about 60 per cent of Google’s revenue thus a chunk of the money that flows to Bermuda must in turn flow to the US to cover the group’s R&D costs. In 2015, Google spend $12.3 billion on R&D so it is likely that the company in Bermuda had to make a payment to cover around $7.4 billion of that.

The Bermudan company does get to keep what’s left and that adds up to a pretty penny but it is wholly wrong to suggest that the starting point of €22.6 billion generated in the Irish company is profit. From this we have seen that in 2015 Google:

- pays out €5.5 billion to the owners of websites on which ads are hosted;

- incurs around €5 billion of staff and expenses (including tax!) in Ireland and its other markets;

- contributed around €5 billion to the R&D undertaken in the US.

After all that is accounted for there was probably €7 billion or so left from the original €22.6 billion in 2015 and this accrued to the company in Bermuda. Does that company have the substance that would justify such profits? No. So where should these profits be taxed? Pascal Saint Amans, head of the OECD’s BEPS project, provided an answer when he appeared before the Oireachtas Finance Committee a few years ago:

Assuming the best action plan translates into domestic legislation in all countries, including the US, the companies in question would be taxable in the US and would not benefit from what they currently enjoy, which is double non-taxation.

Why should the profit be taxed in the US? Because that is where the key risks, functions and assets that make Google profitable are located. It is the US system tax allows the international license to be put offshore for an annual cost-sharing payment.

The OECD would prefer this was profit-sharing with each side getting to keep a share of the profit relative to the risk and value-adding activities that it undertakes. If all the Bermudan company does is provide funding for Google’s R&D activity then all it should receive is a financial return for providing the funding with the bulk of the profit accruing the Google Inc. in the US.

It is US tax that is impacted by the Irish structure. Google’s structure has been put under intensive audit in a number of countries including the UK and France. Both ultimately concluded that the structure was in compliance with their laws. The company itself have said they will alter the structure somewhat but the impact on tax payments remains unclear.

If more tax is to be paid in the market countries then it requires a change to the system. Davide Serra does make an interesting proposal that part of what makes these companies profitable is the data they collect from and on their customers. This could be considered an asset in the market country which could be used to justify greater tax liabilities to those jurisdictions. Something along these lines could happen with, for example, the proposed “digital economy tax” in the EU, but absent such a development the bulk of the tax on Google’s profits is due to the US.

How much tax does Google pay? Lots. But we’ll shift our attention to Facebook. Serra said that if we look at Facebook’s annual reports “I see what's the tax paid, I see the number, it's zero. They post ten billion dollar profit.” Does Facebook pay zero tax on €10 billion of profit?

Facebook will announce their 2017 results later this week but here are the company’s annual income statements for the five years from 2012 to 2016.

We can see that Facebook had a net operating income of $10.2 billion in 2016 and that this was after a tax charge of $2.3 billion. That is a long way from zero. If we look at actual cash taxes paid we see that Facebook paid $1.2 billion in income tax which was just under 10 per cent of its pre-tax income.

Facebook’s cash tax payments have been lower than its tax provision in recent years because it had substantial losses carried forward from its early years when it spent huge sums with little no incoming revenue. These losses have likely been exhausted so it will be interesting to see if there are higher cash tax payments in the 2017 annual report. There likely will be but for 2016 we can clearly see that the $1.2 billion of tax paid is quite a deal more than the zero claimed by Serra.

It’s probably also worth showing a similar table for Google (which also announces 2017 results this week).

Cash tax fell to $1.6 billion in 2016 and on this the company said “the timing of tax payments and refunds had a favorable impact to our cash flows from operations for 2016 compared to 2015.” It is a bit of a guess that the 2017 accounts will likely show cash tax as a per cent of pre-tax income heading back towards the 18 per cent levels that were seen in 2014 and 2015.

But enough of the $12.4 billion of tax that Google paid in the five years to 2016 and back to Serra and his claims that Ireland doesn’t tax certain companies and that “if you have a multinational that is 100 per cent directed outside Ireland, de facto, you are not taxed.” It is not clear but it seems likely he is referring to company residence.

But, this only refers to a company’s tax residence in Ireland, not whether it owes tax to Ireland. If a company has operations in Ireland then regardless of who owns it, where it is controlled from, or where it is resident then it will owe tax in Ireland on the profits it earns in Ireland.

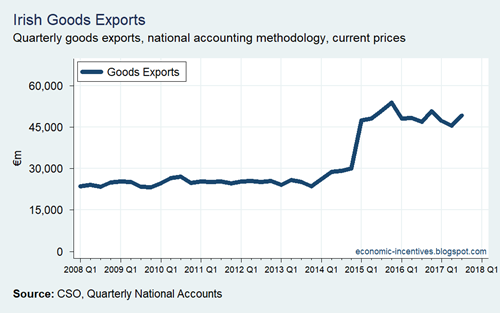

The trouble with Serra’s claim that “you are not taxed” is that, in relative terms at least, Ireland collects a huge amount of Corporation Tax and figures from the Revenue Commissioners show that four-fifths of this is paid by foreign-owned companies. All of these are multinationals that are “100 per cent directed outside Ireland”.

In 2017, Ireland collected €8.3 billion of Corporation Tax. With 80 per cent of that likely collected from foreign-owned companies then they paid €6.6 billion of Irish Corporation Tax.

This notion of foreign companies not being taxed in Ireland is hard to square with the ongoing debate about the sustainability of Ireland’s Corporation Tax receipts at the current elevated levels and the possibility that Ireland is collecting too much rather than too little Corporation Tax. So “de facto, you are not taxed” doesn’t seem so de facto at all.

Here is a 2016 comparison for two EU Member States.

The bottom line is that, in 2016, on a per capita basis, Ireland collected €1,660 of Corporation Tax compared to €560 in Italy. There are lots of reasons to get stuck into for why this might be the case. To think that can be done with tax rates of 0.002 per cent (or even 0.2 per cent) is a joke. As is putting someone on a panel at the World Economic Forum who actually says so.

For companies in general, Serra says “give me one number: total tax paid, where, total number.” Apple got a frequent airing in the debate but no one ever said how much tax the company paid. Here are the company’s income statements for the past six years (year-end is September 30th).

Over the past six years Apple has made $64.5 billion in net cash tax payments (equivalent to 18 per cent of pre-tax income). And Apple have said that they will be paying more tax related to these profits as a result of the recent changes to the US tax code. Is this where the tax should be paid? Again, Pascal Saint Amans seems to think so. And Commissioner Vestager pointed out that her €13 billion ruling against Apple in Ireland would have been lower if the economic value was paid to the US for the R&D activity that takes place there.

Vestager said if Washington chose to tax the profits reported by Apple’s Irish operation, she would reduce her demand accordingly.

The United States could do this by forcing Apple to have its Irish units pay more in fees to Apple in California for the right to license Apple patents.

“If the U.S. tax authority found that the monies paid due to the cost-sharing agreement were too few ... so that they should pay more in the cost-sharing agreement, that would transfer more money to the States and that may change the books and the accounts in the States,” Vestager said.

Does Apple paying $64.5 billion in tax over the past six years and indicating another $38 billion will be paid because of US tax reform mean everything is hunky dory? Absolutely not. But if we are going to be outraged, let’s have that outrage based on what is actually happening not some trumped of version designed to engineer outrage.