Philippe Legrain’s recent book, European Spring, has generated a good deal of reaction in Ireland. Although it is a very broad-ranging book, and a recommended read, the focus in Ireland has been very narrow and mainly has been on the following passage:

For example, had Irish banks defaulted on all their debt at the end of September 2010, German banks would have lost €42.5 billion, British ones, €27.5 billion and French ones €12.3 billion.131

When Ireland was forced to seek a loan from EU and the IMF in November 2010132, the Irish government sought to backtrack on its foolish promise, made in the heat of the post-Lehman panic in October 2008, to guarantee all Irish banks’ debts. Had it succeeded, the doom loop would have been greatly weakened. Instead eurozone policymakers, notably ECB President Trichet, outrageously blackmailed the Irish government into making good on its guarantee, by threatening to cut off liquidity to the Irish banking system – in effect, threatening to force it out of the euro. Thus, having exhausted the borrowing capacity of the Irish government, the creditors of Irish banks could now call on loans from other eurozone governments, along with Britain’s, Sweden’s and the IMF. This was a flagrant abuse of power by an unelected central banker whose primary duty ought to have been to the citizens of countries that use the euro – not least Irish ones. Bleeding dry Irish taxpayers to repay foreign debts incurred by Irish banks to finance the country’s property bubble was not only shocking unjust. It was a devilish mechanism not for the safeguarding financial stability in the eurozone – which would be the ECB’s defence for its actions – but rather for amplifying instability. It entrenched governments’ backstopping of bank debts, sparking fears about countries that had experienced an Irish-style bank-financed property bubble, notably Spain. And it threatened to drag even countries with a reasonably sound banking system, such as Italy, into the doom loop if the situation deteriorated.

The sentiments expressed in the second paragraph here are not in serious dispute. It was the case that the Irish government, through then Minister for Finance Brian Lenihan, did ”raise the issue” of a “dishonouring of senior debt”.

It was then the case that haircuts to senior bank bondholders were ruled out and the ECB had a key role in this though the detail behind the decision are unclear. In the clip above Brian Lenihan indicates that the ECB’s refusal to contemplate haircuts to senior bondholders (presumably only in Anglo and Irish Nationwide) was “unanimous”.

In an interview with The Irish Times in January of this year Jens Weidmann said of the time:

Jens Weidmann: The Governing Council then was weighing bail-in versus financial stability risks, and its majority concluded that the latter were more relevant under the concrete circumstances. In that debate the Bundesbank has always considered it important to make investors bear the risks of their investment decisions and already then favoured contributions of investors in the event of solvency problems, especially for banks that are to be wound down. Our common goal is to be able in the future to wind down banks without endangering financial stability.

But a view opposing such haircuts was previously put forward by Jörg Asmussen in a speech delivered in Dublin in April 2012:

Jörg Asmussen: I know that the decisions concerning the repayment of bondholders in the former Anglo Irish Bank have been a source of controversy. Decisions taken by the Irish authorities such as these are not taken lightly. And the consequences of subsequent actions are weighed carefully. It is true that the ECB viewed it as the least damaging course to fully honour the outstanding senior debts of Anglo. However unpopular that may now seem, this assessment was made at a time of extraordinary stresses in financial markets and great uncertainty. Protecting the hard-won gains and credibility from the early successes in 2011 was also a key consideration, to ensure no negative effects spilled-over to other Irish banks or to banks in other European Countries.

It should be noted that Weidmann did not work for the Bundesbank or Asmussen for the ECB at the time these decisions were made in November 2010 so these are views that were subsequently relayed to them. It is also worth noting that Legrain became an advisor to Barroso in February 2011 so he too was not involved when these discussions took place.

Regardless, it is now clear that the prospect of enforcing losses on senior bondholders in Anglo and Irish Nationwide was ruled out, in large part, at the insistence of the ECB. But it is hard to see how this decision was made to save German, French or UK banks. The decision was made to save the skin/face of the ECB.

In November 2010, the amount of senior bonds remaining in Anglo and Irish Nationwide was around €6 billion. This is a very significant sum in Irish terms but relatively minor in the overall scheme of the European banking system. A 66 per cent haircut on these would have been €4 billion of losses which would be little more than a ripple in the pool of European bank losses (even assuming such banks held all of them).

The impact of the undertaking the action on capital and interbank money markets might have been a consideration but those markets broke down anyway. Little was gained from refusing Lenihan’s request to impose losses on the €6 billion of Anglo/INBS senior bonds.

By November 2010, private banks had relatively little to lose from the bust Irish banks as a result of the repayments made during and, most significantly at the end, of the two-year guarantee introduced in September 2008. But one institution did stand to lose heavily if the Irish banks collapsed (or if Ireland withdrew from the euro). That was the institution that provided the money for these repayments to be made – the European Central Bank.

When the guarantee ended the reliance of the ‘covered’ Irish banks on central bank liquidity shot up. By November the six banks were accessing €88 billion of liquidity from the ECB and also around €42 billion of ELA from the Central Bank of Ireland.

The ECB did not bounce Ireland into a bailout to rescue German banks; it did so to ensure it would not be burned itself. Central bank funding of the ‘covered’ banks was €130 billion in November 2010 and it peaked at around €150 billion in February 2011. These are massive figures in all contexts.

The ECB wanted to tie Ireland into a programme to ensure this was repaid. And they were successful. ECB funding to the remaining covered banks is now down to €23.5 billion while the use of ELA all but ended with the liquidation of the IBRC last February. Reliance on central bank funding by the covered banks has been reduced by 80 per cent.

The first paragraph above extracted from Legrain’s book has some large numbers for potential losses to German, French and UK banks if the Irish banks defaulted in November 2010. These numbers are meaningless in the context of the Irish banking collapse. Footnote 131 tells us where they come from:

131 Bank of International Settlements Quarterly Review, March 2011. Foreign exposures to Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain, by bank nationality, end-Q3 2010, converted from US dollars to euros at exchange rate on 30 September 2010 of €1 = $1.3615.

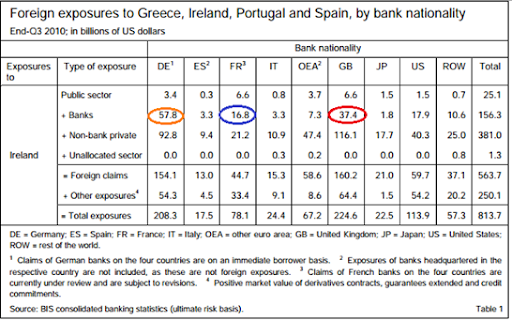

The BIS report referenced can be accessed here with the accompanying statistical annex here. The figures used by Legrain are from Table 1 on page 15 of the report with panel below showing the figures for claims on Ireland with the German, French and UK bank claims on banks in Ireland circled.

For some reason these figures for Q3 2010 are not the online BIS database. The total liabilities of French, German and UK banks to Ireland are available for Q3 2010 but in it is not until Q4 2014 that a breakdown by sector (bank, non-bank private and public) is available from the database.

The table below shows the claims for German-, French- and UK- headquartered banks on Ireland (banks, public sector, non-bank private sector and total) for all quarters in 2010 and 2011 and the sectoral breakdown where available from the database. Click to enlarge.

The first quarter for which the sectoral breakdown is provided in the BIS database is Q4 2010 and the data shows that at that time the amounts owed by banks in Ireland to German-, French- and UK-headquartered banks were $28.5 billion, $8.1 billion and $18.3 billion respectively. These are somewhat distant from the $57.8 billion, $16.8 billion and $37.4 billion figures for the previous quarter shown in the Q3 2010 BIS report. This is not surprising and the reason for the rapid decline is the bank run that happened in Ireland in late 2010.

The figures are precisely true for what they represent: claims of foreign banks on banks in Ireland. The figures are precisely useless for what they are most frequently used to represent: losses avoided by foreign banks from the rescue of the six ‘covered’ banks in Ireland.

One reason is that saying “German banks would have lost €42.5 billion, British ones, €27.5 billion and French ones €12.3 billion” requires there to have been a 100 per cent default which is patently unrealistic. However, the main reason for the inappropriateness of the figures in trying measure potential bank losses that were avoided by the bank bailout is that there was far more than six banks operating in Ireland in late 2010.

The Irish government rescued AIB, Anglo, BOI, EBS, INBS and PTSB. The €64 billion comes from their rescue. Included in the above BIS figures are also Ulster Bank, Bank of Scotland (Ireland), Danske, KBS, Rabobank and other foreign-owned retail banks operating in Ireland.

Most importantly though the above figures include the liabilities of banks operating in the IFSC which have close to nothing to do with the domestic Irish economy (apart from providing employment and paying some taxes) and equally nothing to do with the collapse and bailout of the Irish banking system.

A look at the post on the Irish bank run shows that an almost equal amount of deposits were leaving ‘Other Banks’ (i.e. IFSC banks) and all the ‘Domestic Banks’. In fact, in the last six months of 2010 deposits in banks operating in Ireland fell by €200 billion; the reduction for the covered banks (a sub-group of the ‘Domestic Banks’) was €75 billion. Most of the deposit flight from Irish banks was in those banks not bailed out by the Irish government.

The deposit flight can be seen in the reduction in foreign bank claims on the Irish banking sector in the above table from $148 billion and the end of Q2 2010 to $83 billion at the end of Q4 2010. It is clear it is more than just foreign banks who withdrew deposits from banks operating in Ireland – again with most of that from the non-covered banks.

Whatever the BIS data can tell us, and it is useful in some contexts, it can tell us very little about the exposure of foreign banks to the six bailed-out banks in Ireland. As shown in the table most of the foreign-bank exposure to Ireland is to the non-bank private sector which is likely to be collective investment funds based in the IFSC.

Do we have any insight on the foreign funding used by the six ‘covered’ banks? Yes, from this research note from the Central Bank of Ireland which looked at the foreign-funding of “Irish-headquartered banks”. By and large these were the six covered banks (AIB, ANGLO, BOI, EBS, INBS and PTSB) but did also include some banks active in the covered bank market (Pfandbrief banks) who had their headquarters in Ireland from 2002 to 2011.

The funding of Irish-headquartered banks is usefully summarised in this chart.

The conclusion is pretty straightforward:

Throughout the 2000s the UK remained the predominant source of foreign funding for the Irish banking system, representing 77 per cent of foreign funding by mid-2008. After the UK, creditors in the US and offshore centres accounted for the most substantial shares of foreign funding at 13 and 5 per cent, respectively by mid-2008

Germany was the source of approximately 11 billion or 25 per cent of total foreign funding at end-2002. Thereafter, absolute German funding fell quite quickly to below 5 billion, or 5 per cent, by end-2006 and to below 1 billion or 1 per cent by end-2007. Pfandbrief banks headquartered in Ireland accounted for nearly eighty per cent of this funding.

The relative unimportance of other euro area countries as a source of the Irish banking system’s foreign funding is surprising.

And the chart is done on a residence basis. If Irish banks got funding from affiliates abroad it would be included in the above chart. Most of the covered banks had operations, of varying sizes, in the UK. So if AIB-UK provided funding to AIB in Ireland it is counted as UK-sourced funding in the above chart.

It can be seen in the chart below that almost all of the increase in the foreign funding of Irish banks was from banks (the red line) with most of this from non-affiliates (the blue line) than from affiliates (the purple line).

It can be seen that at the end of bank guarantee funding from non-affiliated foreign banks collapsed from around €55 billion to around €5 billion. This was offset by an equally sharp but temporary increase in funding from foreign-affiliated banks. By the time of the bailout (the middle of the dashed lines) the amount of funding owed by Irish-headquartered banks to foreign banks was very very small.

Of course, the above data doesn’t allow us to pierce through and see where the affiliated foreign banks were getting the funding they were providing to their Irish parents.

All this really shows is that in November 2010 German, French and UK banks were not in hock to the failed Irish banks. The Irish banks did get funding by the UK interbank market but that ended with the guarantee a couple of months previously. At no time did the Irish banks access significant funding from German or French banks.

The ECB did not force Ireland into a bailout and require the repayment of senior bond in Anglo and INBS to save German and French banks; it was done to save the ECB itself which was owed €150 billion by the Irish banks and was trying, and failing, to keep the European banking system fluid. The ECB was ensuring that it got its €150 billion euro back and was trying to save face because as a central bank it can’t go bust.

Philippe Legrain is right to point out that ECB forced Ireland into costly actions such as the repayment of €6 billion of senior unsecured (and by that time unguaranteed) bonds in Anglo and INBS. He is wrong to say it was to save German and French banks. By November 2010, foreign funding from non-banks (c. €25 billion) was much larger than from foreign non-affiliate banks (c. €5 billion) and foreign affiliate bank funding was largest of all. It is likely that most of the €6 billion repaid on those bonds went to non-banks.

Why did the ECB bounce Ireland into a bailout? It wasn’t to rescue German and French banks. It was probably to ensure that Ireland did not have the time to make provisions to put an alternative currency in place. We don’t know if the government had a Plan B in place in November 2010, and even if there it it is likely to have been something that had close to zero chance of actually happening, but the ECB wasn’t going to give them the opportunity to think about it.