The video below is from the EU Council press conference last night at which Commission President José Manuel Barroso had some interesting things to say about Ireland. The question from RTE’s Paul Cunningham that sparked Barosso’s comments begins at 04:45. The question lasts for about one minute. The response continues for nearly five!

Friday, December 20, 2013

Tuesday, December 17, 2013

Fitch on Mortgages

Both the Irish Independent and The Irish Times cover a teleconference given yesterday by Fitch on the Irish economy and the Irish banks. The Irish Times report summarises their conclusions on mortgages as:

The agency expects loan arrears to peak in 2014, and that 40 per cent of loans that are more than 90 days in arrears will begin to “reperform”. Another 40 per cent will be the subject of some type of writedown, with 50 per cent of the debt in this category being written off. The final 20 per cent of loans will see the associated properties being repossessed.

Overall, the agency believes 4.8 per cent of outstanding mortgage balances (ie, €2.2 billion) could be lost by the banks.

If these are applied to the entire market (the Fitch-rated banks in Ireland are AIB, BOI, PTSB and UB as can be seen in this report on Irish banks released earlier in the week) it would mean around 16,000 repossessions in the owner-occupier market.

The most recent mortgage arrears statistics show that there are 99,189 PDH mortgage accounts in arrears of 90 days or more. With an average of 1.25 accounts per household with a mortgage that means that around 80,000 households are in 90 day arrears. A 20 percent repossession rate would be 16,000 homes.

I have suggested similarly before: September 2013 and December 2012 and even back to November 2011. Any resolution of the mortgage crisis is going to involve a dramatic step-up in repossessions which as we saw in the previous post have remained incredibly low.

The relation between the number of accounts and the number of properties in the buy-to-let sector is not known. Unlike PDHs it is possible that one BTL mortgage account could encompass several properties.

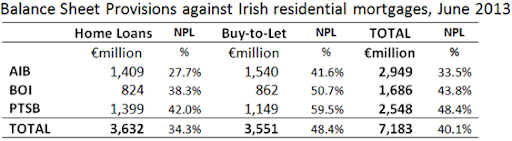

If we just focus on the ‘covered’ banks in which the State has varying equity stakes we see that they had €90.2 billion of Irish mortgages at the end of June 2013 as shown in this table.

Taking the 4.8 percent estimate of the outstanding mortgage balances that “could be lost by the banks” implies a loss of €4.3 billion if applied to the €90.2 billion of Irish mortgages that AIB, BOI and PTSB have.

It is not clear where the €2.2 billion figure in the reporting comes from. Using the figures above the closest fit is that it relates to PDH mortgages in the ‘state-owned banks’, AIB and PTSB: €31.1 billion plus €17.7 billion equals €48.8 billion which multiplied by .048 equals €2.3 billion.

Looking across all three banks the stress scenario three-year loss rate on Irish mortgages used in the 2011 PCAR exercise to calculate the capital needs of the banks was 9.2 percent (7.6 percent for PDH mortgages and 14.3 percent for BTL mortgages). Both are in excess of the 4.8 percent loss rate now projected by Fitch.

The nominal loss on Irish mortgages allowed for under the 2011 recapitalisation was €9.0 billion. Although substantial mortgage losses have been provisioned for very little has actually been crystallised since the 2011 PCAR exercise. As it stands the banks have €7.2 billion of provisions against their Irish mortgages.

Applying the 4.8 percent rate, Fitch estimate that the banks could lose €4.3 billion of outstanding mortgage balances (assuming it applies equally to PDH and BTL accounts). The banks have 66% more provisions than the projected losses estimated by Fitch.

However, the banks are going to have to continue to roll-out restructuring arrangements for the 40 percent of those in 90 day arrears who can get back on track but need a long-term restructuring. Many of these will involve a cost for the banks: permanent interest rate reductions, split mortgages and possibly capital forgiveness (though there seems little willingness on the part of the banks to allow this while the borrowers retains ownership of the property).

These loans may not appears in provisions or crystallised losses but this will involve a cost for the banks and, along with the continuing problem of ‘tracker rate’ mortgages, will hinder the banks’ ability to generate operating profits and bolster their capital base.

In advance of next year’s ECB stress tests Fitch say:

While this (the recent Balance Sheet Assessment undertaken by the Central Bank of Ireland) may reduce the banks‟ end-2013 capital adequacy positions, Fitch believes that once the CBoI’s observations have been considered the banks should be in a better position to withstand EBA scrutiny and tail risks should be reduced as a result of more conservative provisioning against NPLs.

While the banks will likely pass the ECB stress test in 2014 the impact of new capital requirements rules to be introduced over the medium term will be much greater. Fitch conclude:

Applying 2019 Basel III rules, Fitch estimates that Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) would reduce to 5% in BOI and 4% in AIB which is weak in view of the high levels of net impaired loans/equity and underscores the need for these banks to be capital generative through profitability before their credit profiles can stabilise on a sustainable basis.

The banks are going to need more capital over the medium term. A return to profitability is one way to achieve this. Last week’s preference share sale and equity rights issue has shown that BOI can raise some capital from private market sources. The ability of AIB and PTSB do to so remains untested. AIB may begin in 2014 but a long-term restructuring plan is needed before PTSB will be able to do so.

Mario Draghi is right that the Irish banks remain a source of “some concern” but the key concern is not necessarily stress tests or capital ratios in the future (though they are important); the main concern remains the lack of resolution to the distressed loans the banks have now.

Monday, December 16, 2013

Repossession Statistics

The mortgage arrears statistics published each quarter rightfully get a lot of attention but included within the releases are figures which get little attention. These are the repossessions and court proceedings statistics that are also published. The focus here is only on the figures that relate to primary dwelling houses; buy-to-lets are not covered.

One reason they are not covered is that a useful time series of the data is not provided and the relevant numbers are only included in the text accompanying the statistics rather than in tabular form. The following table collate the figures from the quarterly releases to date.

First, is the number of repossessions.

In the last four years 2,386 houses repossessed. Of these, 70% have been repossessed through a voluntary surrender by the borrower. There have been just 738 court-ordered repossessions, less than 200 a year. Given the scale of the mortgage debt crisis we are in this is an incredibly small number.

Of the court-ordered repossessions it has been indicated that close to half are at the behest of sub-prime lenders who make up about 2% of the outstanding mortgage debt.

One important outcome that is missing is where a borrower is pushed into a forced sale of the house by the bank. This does not appear in the repossession figures as the bank does not take ownership of the property but the loss of possession for the borrower is the same. A related issue is what happens to any shortfall that might remain on the mortgage after the forced sale is concluded.

Next, we have the number of court proceedings issued and concluded each quarter.

There was a massive jump in the number of court proceedings issued in the last quarter. This is likely related to the lacuna in the law identified through ‘The Dunne Judgement’. This was recently resolved.

It can be seen that of the court proceedings concluded roughly half end with the granting of an order for repossession (though some are merely to formalise a voluntary surrender) and half are concluded by other means. Most of these see the borrower and lender enter a new arrangement through a restructuring of the original loan agreement with others ending by way of voluntary surrender/abandonment. Again no detail of forced sales is provided.

There have been 1,957 court-orders for repossession granted. There have been 738 court-ordered repossessions over the same period. Some of the repossessions orders are granted to formalise a voluntary surrender/abandonment that has already occurred and even though a court-order is granted the lender and borrower may enter a restructuring arrangement to try and avoid an actual repossession. Although the six-fold jump in the number of court proceedings issued this quarter may change it, there does not appear to be a significant back-log of court orders for repossessions waiting to be enforced.

The third element available is the number of properties that are in the possession of the lenders. This increases with the repossessions of the first table and is reduce by the properties sold shown here.

Over the past four years the lenders have sold just over 1,500 properties which were repossessed as PDHs and continue to have another 1,050 in their possession.

Finally, the figures previously includes the aggregate number of active court proceedings which had been issued and the number of formal demands which were outstanding. These aggregate figures have not been published since the second quarter of 2012.

It is not clear why these figures are no longer reported. Q3 2012 was the first quarter when arrears figures for the Buy-to-Let sector were provided but it may not related.

Ireland’s Regressive Tax System

A recent study from the Nevin Economic Research Institute looked at the combined effective rate of direct and indirect taxes on Irish households along the income distribution. The headline results are summarised in this chart.

The lowest contributions are in the third and fourth deciles and we have previously looked at the composition of the households in those deciles (albeit using the SILC rather than HBS as used by the NERI study).

So what can we say about these estimated tax burdens. The following table gives the estimated nominal amounts paid by each decile.

The estimated average tax burden is €12,900 per household. According to the Census taken in April 2011 there were 1.7 million households in the country. Thus the total amount of tax included in the effective tax rates is €12,900 x 1.7 million = €21.9 billion (of which €12.5 billion is “direct” and €9.4 billion is “indirect”). That is a lot of tax but it is around half of the total tax actually collected in 2010. The 2010 tax take is summarised in this table.

Of course, the incidence of taxation is incredibly difficult to determine. Direct taxes are deducted from income but even that is not enough to isolate the economic incidence of the tax. Do employers need to pay a higher wage to attract workers from a abroad in locations with high income taxes? This is an issue in various soccer leagues. Determining the exact incidence of indirect taxes is almost impossible.

If a household buys something for €123 that includes VAT at 23% then the amount of VAT in the price is obviously €23. However, this doesn’t mean the purchaser paid the full amount of VAT. It depends on what the price would be in the absence of the VAT.

If the VAT was eliminated the price might fall to, say, €110. It is incorrect to say the household has paid €23 VAT when the price absent a VAT would be €110. In this case the retailer, or some other element along the production chain, has absorbed part of the VAT.

The NERI report covers €5.7 billion of VAT (€3,360 x 1.7 million) as opposed to the €9.9 billion actually paid but it is not stated why this gap is present. It could, in part, be because of VAT paid by businesses not fully passed on in the price. Of course, this will be reflected in lower profits and dividends from the business so the burden of the taxation will ultimately be borne by households as is the case for all taxes. Some of those households may be outside the country as with Corporation Tax with around 75% of the total paid by foreign-owned companies.

There will be many small businesses who would regard the rates, excise duties and other taxes which they might not be able to pass on through prices as coming out of their income. Of course, there will also be many cases where rates, duties and other taxes are put into the price but are not explicitly listed. However, in the sense that these may affect all households equally it may not alter the overall results. Then again they may not.

Returning to the household level it is worth looking at the income and expenditure figures for each decile. The tax rates shown in the first chart above are as a percentage of gross income while the dominance of indirect taxes for the lower deciles means that the amount of tax paid is, in the main, a function of expenditure. This table from the report summarises these.

One of the notable features is that average expenditure of households in the lowest decile is almost two times greater than their disposable income. This is also true for the second, third and fourth deciles though not to the same extent.This is not an unusual feature of household surveys and the following is noted by the CSO in their publication of the 2009/10 Household Budget Survey:

There are many reasons why expenditure may exceed income in lower income decile households and this is a common experience internationally in income and expenditure surveys. Households with recently unemployed household members may draw on savings to maintain their expenditures. Self-employed consumers may experience business losses that result in low incomes, but are able to maintain expenditure by borrowing or relying on savings. Third level students may get by on loans or savings from summer employment, retirees may rely on savings and investments. In addition, across all deciles there may be an under-reporting of certain categories of income (e.g. shadow economy employment income).

On the income measure in the HBS the CSO note that:

The HBS [.] calculates income on the basis of the “current income level” of the individual without adjustment for employment activity over the year in question.

The HSB is a weekly survey rather than an annual one with respondents reporting their income and expenditure over a two-week period. Is it appropriate to calculate an effective tax rate using expenditure now when the income may have been earned previously?

In the 2009 SILC the average disposable income of households in the lowest income decile (as measured over a year) was €11,000, around 12% higher than the equivalent figure in the HBS. For the top decile the SILC has a figure of €118,300 versus €119,500 in the HBS, a difference of 1%. The HBS may not the optimum instrument to measure income but it is good at what it is designed to measure: expenditure. Here are the expenditures, estimated indirect tax burdens and effective tax burdens as a percentage of expenditure by decile.

Although VAT has some progressive features with most necessities zero rated it can be seen that the proportion of expenditure accounted for by indirect taxation is inversely related to expenditure. The greater the level of expenditure the lower is the proportion taken in indirect taxes. This is likely due to consumption patterns, particularly in relation to high excise duty goods, and also the disconnect between some indirect taxes and expenditure such as the television license, credit/debit card levies and annual motor tax to a certain extent.

Although there may be difficulties measuring it there can be little doubt that indirect taxation in Ireland is regressive. Whether it is sufficiently regressive to offset the very high progressiveness in direct taxation is less clear cut. Finally, the CSO also give a breakdown of the income by direct income and state transfers for each decile which can be used to infer that Ireland’s overall tax and transfer system is progressive.

Friday, December 13, 2013

The Protected Third Decile

Earlier the week the ESRI published a report that analysed the impact of budgetary policy since October 2008 on household disposable income. It is summarised in this chart.

The commentary on the chart in the report says:

These results do not conform with either a progressive pattern (losses increasing with income) or regressive pattern. (losses declining with income). Over a substantial range (deciles 4 up to and including decile 9 – and also decile 2) the pattern is broadly proportional. But this does not extend to whole income distribution. Contrary to some perceptions of a sharper squeeze on middle income groups, the greatest losses have been at the top of the income distribution, and the next greatest losses at the bottom. Only the third decile had a significantly lower loss (under 10 per cent) than others.

Our focus here is on the final comment. Why did the third decile have a significantly lower loss than the others?

One way to answer this is to look at the composition of households in each decile of equivalised disposable income. This can tell us who is in the third decile. Here is a table that looks at the composition of households by decile in the 2009 SILC. Click to enlarge.

It is pretty clear which households are over-represented in the third decile. Individuals from households with one adult aged over 65 made up 7% of the 12,641 individuals in the households surveyed by the CSO for the 2009 SILC but comprised 22% of individuals in the third income decile. The only other individuals overrepresented in the third decile are those from households with two adults with at least one aged over 65(12% of the sample and 17% of individuals in the third decile).

Combined individuals from these households with adults aged over 65 made up 19% of the sample and 39% of individuals in the third decile.

It should first be noted that the proportions here are those in the survey sample not necessarily those in the population. It is the over/under representation in each decile that provides insight. It should also be noted that the top chart covers changes in disposable income from 2009 to 2014 while the above table of household composition uses data from the 2009 survey only but it is still probably a useful indication of who comprises the protected third decile who have “had a significantly lower loss than others”. Value judgements are left to others.

Aircraft imports take a nosedive

We have looked aircraft imports before and today’s release from the CSO of the Trade Statistics for September further highlight the drop in aircraft imports in 2013.

Imports of large aircraft in the first nine months of 2012 were 51 units worth €2.2 billion. In the same period in 2013 there have been 21 units imported worth €0.7 billion. The most notable changes are the reductions in aircraft imported from Brazil and the United States (which were usefully explained in a comment to the previous post).

The impact of these large changes relative to 2012 is that the balance of trade will be improved and the level of investment (fixed capital formation) will be reduced. The €1.5 billion reduction in aircraft investment will be a significant drag on the measure of “domestic demand” that will be published with next week’s quarterly national accounts but the impact on the ground will be negligible.

Of the large aircraft imported last year 29 units worth €1.6 billion were imported in the first three months. This led to a significant spike in gross fixed capital formation in Q1 2012 in the Quarterly National Accounts that was reversed in Q2.

As item 792.50 in the table above shows imports of spacecraft remain zero. Maybe we don’t need any for the economy “to take off like a rocket”.

Thursday, December 12, 2013

Inflation is near zero but not in all sectors

Today’s CPI release from the CSO puts the headline rate of inflation at +0.3 percent. However, that is being dragged down by mortgage interest (-6.0 percent) and energy prices (-2.8 percent). These make 15 percent of the overall index. If we strip those out to get a measure of ‘core’ inflation we see the following.

Core inflation is running at around +1.0 percent but this in itself is driven by some fairly particular price increases. Details of these are below the fold. The pattern of where the price increases in the Irish economy are coming from should be easy to identify.

Wednesday, December 4, 2013

A profit from the BOI bailout?

This morning Bank of Ireland have announced that they indeed to redeem the €1.8 billion of preference shares held by the National Pension Reserve Fund in the bank. Since the onset of the crisis the State has contributed €5.8 billion to Bank of Ireland. This comprises:

- €3.5 billion of preference shares in February 2009

- €1.3 billion of ordinary shares in July 2011

- €1.0 billion of contingent capital notes in July 2011

That is a total of €5.8 billion. And what has been returned?

In April 2010 it was announced that €1.7 billion of the preference shares would be cancelled as part of a swap with ordinary shares in the bank. That left the €1.8 billion of preference shares in today’s announcement. As part of the swap the State received around €0.5 billion in warrants for the cancellation of the preference shares.

In July 2011 it was announced that around €1 billion of ordinary shares held by the NPRF would be sold to private investors. In January 2013, the sale was completed of the €1 billion of contingent capital notes held by the Minister for Finance were sold.

When the €1.8 billion from today’s announcement is received that will bring the total received from asset transaction to €4.3 billion.

There have also been substantial income receipts from Bank of Ireland over the past four years. These include transaction fees (€0.1 billion), preference share dividends in cash (€0.6 billion), contingent capital interest (€0.2 billion) and various guarantee fees (€1.5 billion). These total €2.4 billion.

Thus total receipts from Bank of Ireland over the past four years are €6.7 billion which is a surplus of almost €1 billion over the €5.8 billion put in.

It can be seen though that the “profit” only arises with the inclusion of the various guarantee fees and not simply from the financial transactions with Bank of Ireland. These were a ‘fee for service’ and providing the guarantee was not a costless operation for the State. Only monies paid to Bank of Ireland are included while costs carried by the State (higher interest rates, reduction/elimination of market confidence) are ignored. It is probably appropriate to omit the guarantee fees when determining the profit/loss from the State’s financial transactions with Bank of Ireland.

That means we are still nursing a €0.6 billion loss. However the State still holds a 15 percent equity stake in Bank of Ireland (which will be diluted slightly by today’s announcement if the State does not participate in the rights issue). With a current market capitalisation of around €8 billion this stake is worth around €1.2 billion. We may yet turn a profit on the bailout of Bank of Ireland.